The following text is the third critical review of a book by the philosopher Julio Cabrera.

The first one addressed his outstanding book A Critique of Affirmative Morality.

The second one addressed his book Because I Love You, You Will Not Be Born!

And this one addresses the book Introduction to a Negative Approach to Argumentation – Towards a New Ethic for Philosophical Debate.

After criticizing what he refers to as ‘affirmative ethics’ and the very possibility of being ethical in his monumental book A Critique of Affirmative Morality, Cabrera criticizes what he calls ‘the affirmative approach to argumentation’ and the very possibility of making a universally true argument that everyone must logically accept. In a way, his book about affirmative morality is kind of lamentation for ethics, and the book which is the subject of this text does a similar thing to argumentation. In his book about ethics he writes that morality necessarily leads to an impasse, and in this book that argumentation necessarily leads to an impasse.

The Affirmative Approach to Argumentation

Cabrera is critical of philosophy’s ‘Affirmative Approach to Argumentation’ which according to him seeks a unique universal “truth” in argumentation while aiming at proving wrong any opposing view or the option of several “truths”.

Cabrera wonders how is it that the greatest minds of all history haven’t yet reached the right answer about so many philosophical questions, and suggests that it is because so far philosophy aimed at one true answer and rejected the possibility of multiple answers.

“The “affirmative approach” consisting basically of thinking that philosophical queries have a right solution, or, at least, an adequate approach among many others that are inadequate or wrong. What we notice, even with “great philosophers” in classic and present times, is a remarkable concentration on their own positions, as they maintain a strong belief that they are providing an adequate approach to the debated questions and they reject, sometimes summarily, the alternatives. The affirmative approach sustains a meta-philosophical view of the plurality of philosophies as a scandal and a mistake which must be resolved in some way.” (Page 4)

And the way philosophy suggests to resolve that mistake, is according to Cabrera, by an affirmative argumentation process. Any argument theory has to go through six steps, one way or the other, which are:

(1) Determining the existence of an argument – first there is a need to check whether there is, in fact, an argument at all, as it could be that the case is of an unstructured mixture of statements, or a declaration of intentions, or an emotional expression.

(2) Determining the existence of an arguer – there must be someone who advances the argument and defends it, taking the burden of proof and assuming the responsibility for the argument.

(3) Reconstructing the argument – the arguer has to try to reconstruct the argument in question through argumentation schemes showing whether there is only one argument or many, which argument is central, whether an argument is a sub-argument of another, which are the relevant premises and which are the expected conclusions and so on.

(4) Making terms and premises clear – the arguer has to question whether there are terms to be clarified or defined in the reconstruction carried out in step 3; it is also necessary to expose the assumptions and the premises whose truth will be accepted without argument.

(5) Testing the argument’s correction – do conclusions effectively arise from premises and assumptions? How about the quality and reliability of the inferential passage? Is the argument convincing, cogent, overwhelming? Does it set forth its conclusion?

(6) Testing the aims of the argument – the argument might not have any impact on the audience being targeted and in that case, if purposes are not accomplished, the argument fails. The agreement or assent of the target audience can be crucial to many types of argumentation and, perhaps, to all of them.

The main reason Cabrera criticizes the affirmative approach and suggests an alternative approach to argumentation, is not because of fundamental flaws he inspects in the above formulation. He agrees that this is basically how argumentation should be performed, however he is crucially concerned with what actually happens in real philosophical arguments.

Cabrera inspects a major flaw in the affirmative approach to argumentation not necessarily as a result of major flaws in formal or informal logic, but in the insistence that inspecting arguments with ideal norms of logic would provide one right answer that no one can counter argue, a scenario that according to him never happens, and can never be guaranteed.

The affirmative approach to argumentation is affirmative in the sense that according to it, the answer to the question – can philosophical questions be resolved by argumentation, is affirmative, while according to Cabrera the answer is negative.

Naturally, each side of the argument aspires to assume the best arguments, but according to Cabrera an argument can be considered right or wrong only from a certain perspective, and there is no neutral or objective authority (such as God or a super-computer) that can decide between different perspectives as to which of them is the unique one for solving the philosophical issue.

Therefore, according to Cabrera, endless confrontation and conflict between arguments and counter-arguments is intrinsic to the very process of argumentation, which usually ends in an impasse.

Cabrera emphasizes that the problem is not necessarily that argumentation does not follow rules, but that in each one of the six steps of argumentation specified above, each side can use each step to open new lines of counter-argumentation, following the rules. Cabrera exemplify:

“Let’s take, for instance, step number 1, the very existence of an argument. From certain perspectives and assumptions there exists an argument which is perfectly inexistent from other perspectives and assumptions;”. (page 21) According to Cabrera whether there is a real issue to be subjected to argumentation is not something that can be decided in absolute terms, and he exemplifies: “in a debate on abortion, for example, the very “abortion problem” might not even exist for a religious arguer who considers the criminal nature of preventing the development of a foetus totally evident. For him, there is nothing to be argued at all.” (page 21)

And indeed we see that quite often in antinatalist debates, many pro-natalists are not convinced that there is a problem to begin with. As far as they’re concerned, life is good and it is good to make more of it.

And that’s only the first step. The second step – who has the burden of proof, is another example for something we often encounter in antinatalist debates as many antinatalists argue that the burden of proof is on the people who choose to procreate since the burden of proof applies to anyone who makes a positive claim, and pro-natalists simply presuppose that procreation is good despite that it was never questioned, let alone proven to be good.

Pro-natalists on the other hand argue that the burden of proof is actually on antinatalists as they are the ones who are challenging a perceived status quo, they are asking people to stop doing something so natural and that was done since forever.

Cabrera argues that the “Affirmative approaches to argumentation assume a highly rational conception of a human being, as a cooperative agent disposed, in principle, to engage in a critical discussion aiming for a reasonable solution to differences via argumentation and, when necessary, leaving their subjective and personal interests aside.” (Page 54), while actually and frustratingly, everything can be, and practically is, counter-argued according to the motives and the perspective of any opponent to any position.

In Cebrera’s words:

“Whatever our attitude may be concerning these stances, however unusual or even extravagant, one cannot deny that the defenders of these positions are able to advance arguments in their favour that can be regarded, under certain assumptions, as strong and deserving of reply. It is always possible to oppose an argument. Therefore, the very notion of a “counter-argument” must change in the negative approach, because counter-arguments are always available for any given argument; if counter-arguments are not advanced, this is not due to strictly argumentative reasons. There seems to be no argument without potential counter-arguments. Terms, premises or sequiturs can always be challenged or rejected, however well-defined or “sound” they may appear to their defenders.” (Page 24)

And to make things even more frustrating he argues that:

“The same way that it is possible to look at something without really seeing it, or hearing without listening, so it is possible to understand one concept without thinking with it; in a sort of conceptual blindness. Similarly, as some visual organizations of pieces make some particular perceptual associations easier and others more difficult, some organizations of concepts promote some specific kind of thinking and make others difficult or even block them completely.” (Page 33)

So according to Cabrera: “An informal logic theory that applies only to cases where there are expressive agreements at the point of departure, and therefore high expectations that one side will simply accept its defeat at the end, seems a rather narrow scope theory.” (Page 71)

In reality crucial problems do not arise only because and when arguers “do not follow the rules” or because they “commit fallacies”, but disagreements, misunderstandings and impasses are or can be preset at every moment during the process of argumentation, even when all the rules are strictly followed.

For these reasons and more, he argues that the affirmative approach to argumentation is false and a negative approach to argumentation is needed.

The Negative Approach to Argumentation

The fundamental ideas of the negative approach are as follows:

Arguments cannot be solved in a unique, correct way. Arguments can be solved correctly in many different ways. Contradictory conclusions don’t eliminate each other but both may be true at the same time, according to their own conceptual organizations (Gestalten), as long as they follow the steps required to present a possible line of argument. There are many ways of being right and not only one. There are always other lines that can act as a counter-argument to the line initially presented, therefore philosophical discussions are endless.

In the negative approach, the other arguers are not enemies who, with their lines of argument come to destroy mine, but only arguers who reason following other possible lines of argument, and that, from other assumptions, reasonably arrive at other outcomes different from mine.

The domain of argumentation therefore has no self-support. (Page 37)

And the general features of the negative approach to argumentation are:

“(1) We do not know what reality is, or even whether it is unique or multiple; but we know that reality presents itself as shattered and organized in many ways, all of them subjective, none of them unique. (The ontological thesis.)

(2) The different philosophical theories unveil and point to different aspects of reality, but only from their respective organizations. Thus, none of them fails, all of them succeed. They only fail in their attempt to depict the sole truth, transforming their perspective in “what the world really is”. (The epistemological thesis.)

(3) All philosophical theories are tenable in their own terms and they are systematically wrong or inadequate in other theories’ terms, but there is no neutral domain where this tenability could be conclusively and absolutely settled or decided. (The logical thesis.)

(4) Our theories are only perspectives among others, positions among others, without any kind of privilege. They are not the best theories just for being our theories, and they are not correct just because we were able to formulate them properly. In the negative approach, the impression that one’s own theory must be the best and others’ wrong, is nothing except a psychological delusion with no logical support. (The psychological thesis.)” (Page 39)

As opposed to the affirmative approach which assumes that at some point one arguer must prevail over the other by providing the better arguments, the negative approach sustains that all arguments have flaws that can always be stressed by counter-arguments. And counter-arguments according to Cabrera, can’t eliminate or rebut the arguments they challenge since they too are only additional arguments in the web of arguments. They can only reshape, reformulate or relocate an argument in relation to other arguments.

In that sense, and given that there is no external objective unbiased authority that can decide, philosophical discussions according to the negative approach are virtually endless. They end as a result of fatigue, frustration, lack of motivation or interest and etc., but not because one of the standpoints rebutted and eliminated the other.

Therefore Cabrera’s negative approach aims to:

“present and develop the logical position that we assume when we learn to “look around” beyond our own stances, seeing the alternative and decentralizing our own viewpoint, abandoning the intention to occupy the privileged space of unique truth. The negative approach prefers to place ones’ own perspective within a very wide and complex holistic web of approaches and perspectives that speak and criticize mutually without discarding one another, even when each position may fiercely maintain its own perspective supported on defensible grounds.” (Page 5)

One of the problems with that aim is that it is technically impossible to really get out of one’s subjective view. In the best case, one can only realize that its view is subjective and there are other views which might be right just as much from their point of view. But there is no real option for “decentralizing our own viewpoint” as each person’s view is necessarily a centralized one, even the very view of decentralizing one’s own viewpoint. Even when a person is trying to view others’ views it is done from that persons’ viewpoint. No one can really launch itself to other people’s conceptual organizations (Gestalten) and assumptions. This approach can be a good practice for understanding others and even to convince others of one’s own viewpoints, but these are public relations and activism claims, not philosophical ones. The problem of the centrality of our own viewpoint and its effects on the way that everyone absorb information and other viewpoints, can’t be solved by stating there is a need to “decentralizing our own viewpoint”, as this is by definition a mission impossible. It can be effective against dogmatism but it can’t be a recipe for how to do philosophy since if the idea is that every philosophical position is necessarily a result of the standing point of the person holding that philosophical position, then the look on other philosophical positions would still be from the standing point of the person looking at other positions. The decentralization would necessarily remain centralized. We need a decentralization of the decentralization to really decentralize our own views. This aspiration is an endless regression of decentralization.

But of course, the main problem with the negative approach to argumentation is not that it is technically problematic, but that it is utterly ethically problematic, being too tolerant towards alternative viewpoints no matter how cruel and harmful they may be. That flaw is clear to Cabrera who argues that the opposite approach is worse:

“In affirmative approaches, the crucial problem is to be too intolerant concerning the alternative. The crucial risk of negative approaches is just the opposite, being too lenient about them. Both approaches are problematic, and must decide not by a totally risk-free approach, but by a risk we are well equipped to deal with. The option taken by this author is that it is better–logically and ethically–to have an excessive tolerance than an excessive intolerance. But this is not absolute either, just an option in a world where there are no absolute and risk-free solutions totally satisfactory to all parties involved.”

However, I am not sure that the case is of the negative approach to argumentation merely being excessively tolerant. I think that for many it may seem as a theory that goes way further than that. Cabrera understands that his approach may be interpreted as a form of, or at least as supportive or an intensification of Moral Skepticism, Ethical Subjectivism, Moral Relativism and even Moral Nihilism, so he tries to explain why it is none of the above.

To not make this text too long and too complicated, as well as not to deviate from the main and more interesting issue of the book, I decided to add an appendix to this text with some relations to the issue of the negative approach to argumentation being too tolerant to the point of Ethical Subjectivism, Moral Relativism, Moral Perspectivism and etc. You can find it here.

So assuming, at least for the sake of the argument, that the negative approach is truly none of the above, its derived practical conclusion is still very disappointing. Similar to the book A Critique of Affirmative Morality, in this book as well, the criticism is super radical and the descriptions of reality are very sharp and raw, however the conclusion is feeble and deficient. After shredding affirmative ethics and any option to live ethically in A Critique of Affirmative Morality, his conclusion and suggestion derived from negative ethics was merely ontological minimalism. And in Introduction to a Negative Approach to Argumentation, his conclusion and suggestion derived from the negative approach to argumentation is merely a pluralistic stance towards other philosophical ideas and adopting what he calls the Tragic Negativism.

Tragic Negativism

According to Cabrera, argumentation is not a scene of debate between right and wrong but actually a tragedy:

“The attitude that I prefer to assume in this book concerning the negative approach to argumentation is in-between nihilism and indifference. I call it argumentative negativism. It could also be called tragic negativism, in the sense that the difference between tragedy and drama is that in drama one of the parties is good and the others are bad (heroes and villains), whereas in tragedy we find good people on both sides. This means that, in tragedies, someone good and fair will inevitably suffer or die. In the domain of arguments, tragedy appears when we know that we are rejecting a perfectly plausible and tenable posture; we reject it not for being bad, but because we prefer to sustain another perspective maybe incompatible with the other. Like in tragedies good people die, in tragic argumentation good lines of arguments are rejected.” (Page 182)

The tragic arguer is aware that:

“there are dozens of circumstances and contextual elements of character, prevailing values, education, influences, simplicity, fertility, life assistance, social or cultural pressures, pure aesthetic taste, laziness, error, etc., which lead us to prefer one philosophical position over others. We are not driven to it only by the pure force of reasoning; and if somebody demands that we justify our presuppositions, new lines of argument will have to be opened.” (Page 185)

Having said that, according to Cabrera, the negative approach doesn’t mean one cannot adherently hold moral positions:

“The negativist view does not prevent us from arguing vehemently and convincingly in favor of some position to which we strongly adhere. We, for instance, may take a position in ethics favorable to pointing out the moral problems of procreation, abortion, the value of human life and correlated objects we can take a very determined stance on these issues and others, putting all kind of objections to optimistic postures concerning human life. But we do this because we decided–for a series of reasons–to take this line of argument and not another, not in order to defend an objective, unique and irrefutable truth, eliminating alternatives. We simply feel ourselves affectively and intellectually very close to this type of position and adopt it. (although this offends our intellectual narcissism: we would have preferred to have chosen our positions based on deep and necessary reasons.)” (Page 186)

But I don’t understand how one is supposed to adherently advocate for moral positions realizing that others may be right from their own standpoints? If they are right then I am wrong trying to convince them. The negative approach says that it is ok to vehemently hold moral positions while it’s supposed to neutralize or at least dramatically weaken any attempt to convince others, because from their own standpoints they might be right.

People can’t adherently advocate for moral positions under the realization that their position is just another one among many other ideas and it might be wrong just as much. It indeed might lead to indifference, as Cabrera suggests, or to a mental state in which argumentation is actually an intellectual mind game, a rhetoric contest, instead of a crucial ethical discussion.

And evidently Cabrera writes that “Discussions do not have to become a matter of life and death.” Only that all ethical discussions are matters of life and death. It is not the only peculiar claim in the book but it is probably one of the strangest as it is coming from the person to whom mortality is of the most central arguments against procreation. How can a discussion about procreation be anything other than a matter of life and death? And obviously you don’t have to include mortality as one of your central reasons for being an antinatalist for it to be a matter of life and death, as it is in the name. Regardless of the mortality issue, creating a new life is by definition a matter of life and death. And the same goes for abortion, ending life, capital punishment, animal rights, racism, feminism, and every other important ethical issue. They all are matters of life and death and that’s how we must treat them in ethical discussions.

Perhaps Cabrera’s cynical approach comes from his position about argumentation’s origin:

“Arguing is part of our mechanism of survival; we need to argue as much as we need to breathe. Argumentation aims to construct a position that is both an expression of our personality and an explanation of some relevant aspect of reality. In this delimitation of my own argumentative space, the animal drive of life makes me want to destroy other positions or show they are wrong and should be replaced by mine. Thereby I fail to see that others are doing the same as I do: expressing themselves as singular beings, constructing their values, trying to point to aspects of reality from different perspectives. The problem is that such constructions are mutually opposed and this fact encourages the idea that one of them has to prevail over the others by eliminating or replacing them.” (Page 190)

In other words, arguments are mostly if not entirely about the arguers and hardly if any about the issues. People do not use arguments simply for the pure desire to “resolve differences of opinion”, but as a form of defining themselves. They choose values to distinguish themselves, and are using argumentation as a form of expressing themselves and creating rapports with other people.

In Cabrera’ words:

“being a good arguer powerfully increases our self-esteem, especially through the victories we reach in discussions. The rational conception–the more usual in books of logic, even informal–address humans as if they were in a very comfortable and controlled situation where they can be reasonable and objective, with little sensibility to the frictions and insecurities of existence, to the uneasy and arduous domains where humans have to make their arguments through crucial decisions while trying to build their own value.

In logical studies, in particular, we easily forget that we are human animals, sensible beings with a vulnerable body and urgent needs. Our argumentation practices are not placed in a clean and quiet heaven but in concrete circumstances of hard living. We are forced to be defensive and expansive (and even dangerous in some situations) to others; we cannot be totally objective or neutral, but we need to be partial (or even tendentious) in order to survive, not, say, by hunger or physical pain, but by the need to protect our intellectual productions and to create an intellectual prestige within our very demanding communities; we need good self-esteem and intellectual recombination in the same way we need bread.” (Page 57)

I am not yet cynical enough to think that about all arguments, but I agree that this description is unfortunately mostly true.

And I also agree with the pessimistic premise of the negative approach to argumentation that arguments are never resolved, let alone universally and permanently:

“Two human beings engaging in a discussion about philosophical question are naturally and perforce going to differ in substance and method on almost any topic. What is the point in trying to impose one’s own perspective? I see no reason for trying to destroy the other’s lines of thought, even if regarded as absurd, untenable or dishonest.” (Page 6)

Of course there is a reason for trying to destroy the other’s lines of thought but not because it is absurd, untenable or dishonest, but because the other’s lines of thought might be extremely harmful. What is the point in trying to impose one’s own perspective? The answer is that maybe it would reduce suffering in the world.

But the more interesting and relevant question is not if there is a reason for trying to destroy the other’s lines of thought but is that option reasonable? And the answer in most cases is unfortunately No. And if two human beings engaging in a discussion about a philosophical question are naturally and perforce going to differ on almost any topic what is the point of having it in the first place?

A Psychological Negative Approach to Argumentation

You don’t have to agree with Cabrera’s radical philosophical argument regarding argumentation, but you have to agree with what can be seen as a radical psychological argument regarding argumentation.

“The crucial phenomenon is that, whatever our topic of reasoning, the opponent will have always a reply at hand, and we will have a reply to his/her reply if we are not prevented from counter-arguing by external means (violence, illness or death). Even the most seemingly indefensible stance, which would appear to have been totally impaired and unable to provide a counter-argument–by the accumulation of evidence–can always emerge from the ashes and present a defense.” (Page 18)

That means that even if we’ll be able to construct a much more valid and coherent argument than our opponent (which might construct a poor and incoherent argument), as far as the bottom line goes, it doesn’t matter if Cabrera is right that we don’t convince the other side because s/he is actually right from its own perspective or despite that s/he is wrong, as practically we are failing in convincing others.

I disagree with Cabrera that the reason we fail to convince others is because their arguments are right from their perspective. I think the reason is not their philosophical arguments but their psychological motives. Cabrera criticizes the affirmative approach for treating people as rational beings but it seems that he is making the same mistake. Most people are not convinced by our arguments because they are motivated to sustain their positions which reflect what they desire, not because they see things differently and cannot see them as we do.

It seems that he thinks that different stances can be equal in a metaphysical and logical sense and I think they can’t. But I do think they can be equal in a psychological sense. Meaning, different standpoints can be right or wrong from an objective and logical point of view, but at the same time the very same standpoints can be equally strong from the psychological point of view of each arguer, in the sense that opposite sides can hold different standpoints in an equal strength despite one being philosophically weak and the other philosophically strong. I am not a pluralist when it comes to moral stands but I believe that my opponent may hold its stance in an equal strength to me holding mine, and that we can never resolve our argument as long as the motivations differ.

Even if, like me, you disagree with the negative approach to argumentation on the philosophical level, you must agree that there is certainly much value in its arguments on the psychological level. Even if, like me, you disagree with the philosophical argument that the other side may always be right because it has its own perspective on the issue, clearly the claim that the other side won’t be convinced because it has its own perspective on the issue, is almost always right. I don’t think that it stems from one side holding an argument that is as rational and as valid as the argument of the other side, but from having as strong motivation to keep its arguments as the other side. And strong motivations are stronger than strong arguments, since arguments at least theoretically can be reconstructed, but it is hard to change a motivation, let alone using rational tools. The power of pro-natalism is not argumentative but motivational.

I don’t share the view that it is impossible to defeat arguments, but I do think that it is almost impossible to defeat motivations.

Cabrera argues that just like in the case of ethics:

“the affirmative approach thinks that ethical defects are the product of some internal malice of human beings. The negative approach to ethics holds that it is the external situation in which humans are placed that causes ethical defects. It is not that humans were placed in a good world that they destroyed, but they were placed in an adverse world whose difficulties cannot be morally resolved. The same occurs in logic: the affirmative approach holds that arguments can be perfectly resolved, but that humans obstruct this resolution with their fallacious behavior. The negative approach to logic holds that humans were placed in a situation that cannot be resolved by argument, where any argument they present will have to face endless counter-arguments.” (Page 41)

Cabrera seems to blame the situation and not the people, but it is not as if people yearn for the truth only that the truth doesn’t exist, but that people are not really that into the “truth”. They are into what they are into and if that is opposite to the “truth” then not their desires but the “truth” is compromised for the sake of the desires. When people encounter an inner conflict they usually rearrange the “facts” so they would suit their desires, not the other way around. People are not truth seekers, they are motivated by inner psychological and biological derives.

People are not the major victims of the state of moral impasse, the creatures who people severely affect, are. Even if the situation would change, for example by developing a super intelligent entity that would function as an external objective authority which would make moral decisions for people instead of them arguing forever, people’s motivations would still prevail. For example, people don’t eat meat because their Gestalt makes them think that this is the right thing to do, evidently, different people from similar Gestalts, reach different conclusions regarding eating animals. People eat animals because they want to, not because they think they ought to. The same goes for procreation. People don’t breed because they think it is the right thing to do, in fact most breed without thinking it over at all. And they do so because they want to and are built and designed for it.

People’s positions are founded on the basis of their desires, not the other way around. Humans rationalize their desires, their desires are not a product of their reason.

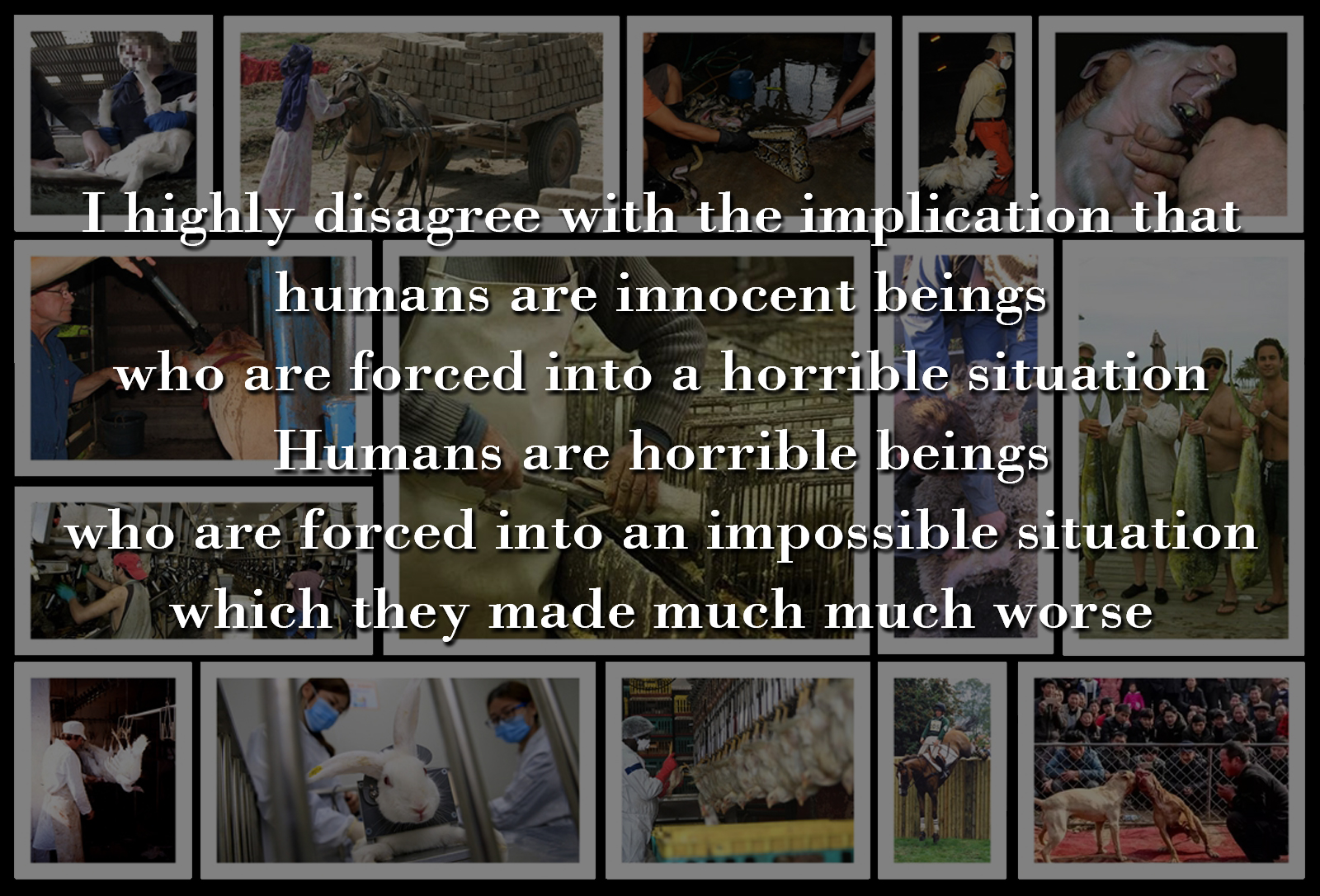

I highly disagree with the implication that humans are innocent beings who are forced into a horrible situation, and think that they are horrible beings who are forced into an impossible situation which they made much much worse. However, the bottom line of the case in point is that it is truly a situation that cannot be resolved by argumentation.

People are forced into a situation in which they are asked to make claims about moral issues as if they are objective, nonbiased, non-motivated, weren’t educated and indoctrinated in certain ways, and have no prior information and inclinations – despite that it is impossible.

I don’t exempt people from responsibility as most of them are lazy, ignorant, shallow, and are not willing to make even the tiniest effort to educate themselves or even listen to the other side before making judgments, however, I agree that even if they did, the situation would still be impossible.

Cabrera’s statement in the last quote is an admission of a known in advance failure. And therefore a very good reason to never procreate. Even if you are sure that humans are innocent beings who are forced into a horrible situation, and all the more so if you agree that humans are horrible beings who are forced into an impossible situation which they made much much worse, in any case antinatalism is the self-evident conclusion. People must stop procreating so to avoid the need to determine moral issues which they anyway can’t resolve.

That argument may sound contradictive as seemingly this is a determination in favor of antinatalsim derived from the inability to make an argumentative determination, however, I am not claiming here that we must determine in favor of antinatalsim because it is the right moral stance (although in my view obviously it is), but because we must avoid the need to determine moral issues since it is impossible according to the negative approach, and antinatalsim eventually leads there. From that perspective, antinatalism is merely the mean to avoid the inevitable impasse consequence of trying to determine moral issues, and not a decision in favor of a specific moral stance.

Another aspect of the impossibility of ethics is, as before mentioned, that as opposed to the affirmative approach, in the negative one “arguments can be carried on indefinitely by both parties, not only because participants are strategic, fallacious or acting in bad faith, but because arguments and counter-arguments can always be advanced from each party without reaching a strict argumentative solution.” (Page 42)

If the fact that argumentation is bound for eternal dispute without ever being resolved had no negative effect on anyone in the world, then existence would still be senseless, purposeless, pointless and amoral, but at least not so ethically horrifying as it actually is. The fact that moral discussions are bound for eternal dispute without ever being resolved and they do have a tremendous negative effect on trillions of sentient creatures, is what makes Cabrera’s claims additional reasons to why this world can’t be morally justified.

The idea that there is no real option to conduct philosophical discussions, especially ethical ones, shouldn’t derive to pluralism but to fatalism. The fact that humans are incapable of understanding the world they live in, and are totally incapable of reaching agreed upon moral decisions, has dire consequences that daily affect billions of suffering creatures.

Although I disagree with Cabrera’s philosophical pluralism conclusion, I do agree with most of his claims regarding argumentation from the psychological angle. Therefore I see no point in addressing the general public, trying to convince each person to be an antinatalist. Instead, I am trying to convince antinatalists to forsake the futile attempt of addressing the general public trying to convince each person to be an antinatalist, and focus on ways to make the general public antinatalist regardless of each person’s opinion about antinatalism.

Due to all the reasons Cabrera specifies along the book regarding the pointlessness and impossibility of convincing everyone to accept a certain position no matter how right it is, I am calling antinatalists not to be ‘tragic arguers’ but effective activists. Desert the senseless attempt to change the minds of all people and focus on changing their reproductive parts. We will not prevent procreation by argumentation, but we might do so by non-argumentative means.

Cabrera ends his book with the following paragraph:

“Ultimately, maybe argumentation is not the proper field for deciding crucial questions (as, say abortion, the abolition of slavery or the death penalty); argumentation does not occupy, as traditionally said, the place of reason and objectivity, but a new place for human passions and a will to expand, now expressed in rational terms. We may be totally convinced of our point of view (for example, that in abortion we always kill a human being, that the abolition of slavery was not due to ethical reasons but to economic calculation, and that the death penalty offends human dignity). We can sincerely think that our arguments are really stronger than the opposite ones and see them as simply displaying the truth and rejecting error. But the brute fact is, that in front of us there is always the possibility of another arguer having counter-arguments and oppositions to each one of our points, and that we have no neutral space to decide that our strong convictions definitively settle the matter. This may suggest that argumentation is not the ultimate domain to resolve differences, especially when they are strongly controversial; that a domain beyond argumentation should be opened, not eliminating argumentation but going beyond it in a way that is different from merely kicking the board.” (Page 195)

Given that the “game” is pointless and absurd, and that it is not at all a game but a real immense and endless tragedy, kicking the board is exactly what we must do. I totally agree that argumentation is not the proper field for deciding crucial questions and that a domain beyond argumentation should be opened, but not one that is different from merely kicking the board, but one which aims exactly for that – kicking the damn board so hard that no sick game could ever be played again.

References

Cabrera Julio, A Critique of Affirmative Morality: a reflection on death, birth and the value of life

(Brasília: Julio Cabrera Editions 2014)

Cabrera Julio, Introduction to a Negative Approach to Argumentation – Towards a New Ethic for Philosophical Debate

ambridge Scholars Publishing 2019)

Leave a Reply