The following is the second part of my reply to Phil Torres’s article Can Anti-Natalists Oppose Human Extinction?

A quick reminder, Torres suggests a ‘no-extinction anti-natalism’ position for “people who, like myself, are sympathetic with the moral prescription not to procreate but are also inclined to think that human extinction would constitute an immense tragedy”.

In the first part I have addressed the arguments against human extinction that Torres specifies and finds convincing. In the following text I’ll focus on his attempt to avoid an internal contradiction in his ‘no-extinction anti-natalism’ position, as well as on the life-extension technologies he details and the various harmful possibilities involved in them.

Harming Humans, and Infinitely More Nonhumans, to “Save” Humanity

Since Torres is convinced by the arguments against human extinction as well as by the arguments against human procreation, he suggests his ‘no-extinction anti-natalist’ position, that calls to stop creating more people, while actively promoting the development of safe and effective life extension technologies that will grant the final human generation functional immortality, and so avoids human extinction.

He details two main ways that can achieve functional immortality. One is called “whole-brain emulation” or “mind-uploading,” which I’ll elaborate about later, and the other way is extending life through biomedical anti-aging interventions:

“For example, geroprotectors are drugs that decelerate aging; the anti-diabetes drug metformin, for example, has been shown to reduce “all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control” (Campbell 2017). And lifelong caloric restriction has been observed to “considerably [extend] both the healthy and total life span of nearly all species in which it has been tried, including rodents and dogs” (de Grey 2004, 724). A more speculative possibility involves what Aubrey de Grey calls “strategies for engineered negligible senescence” (SENS).

There are nine primary types of deleterious, cumulative changes that are associated with aging: cell loss (without replacement); oncogenic nuclear mutations and epimutations; cell senescence; mitochondrial mutations; lysosomal aggregates; extracellular aggregates; random extracellular protein cross-linking; immune system decline; and endocrine changes (de Grey 2003). Interventions to halt or reverse these changes using CRISPR/Cas9 and other synthetic biology systems could thus potentially halt or reverse senescence itself.” (p. 16)

Torres argues that for someone to attain functional immortality it is not necessarily needed that the senescence-stopping technology would be fully realized before or soon after its creation, and it is because of the idea of “actuarial escape velocity” (AEV), which refers to the defined moment when advances in new anti-aging interventions occur faster than one ages, using previous anti-aging interventions. So it may be the case that from a certain point, a person only needs to live long enough to live forever.

Torres speculates that AEV won’t arrive until 2110. Given an average lifespan of 80 years, by then, most people born today will die. That means that humanity would have to keep procreating, which is in opposition to his ethical stance against procreation, in order to achieve functional immortality, which is in accordance with his ethical stance against extinction. And Torres, whose antinatalism relies on Benatarian arguments, knows that he can’t justify further procreation to avoid human extinction for the sake of people who don’t yet exist, but only for the sake of people who already exist. In other words, procreation can’t be justified unless creating new people somehow reduces harm to already existing people. So he suggests to exploit this line of reasoning as a work-around to the problem of creating new people to reach AEV, if that were to be necessary. And he claims it can be argued to be necessary considering the suffering of the last generation, suffering that according to him functional immortality can prevent.

He suggests that all is needed is for three more generations to procreate in order to reach AEV:

“if the length of a contemporary generation is ~25.5 years, and if the average lifespan remains at ~80 years, then the last humans on a phased-extinction schedule would die in about 131 years, circa 2150. In other words, children born today would have children in 25.5 years, these children of children would have children 25.5 years later, and these children of children of children would refrain from having children but live another 80 years.” (p.21)

Although I don’t accept the anti-Epicurean position that death is bad for the person who dies (as explained in the text about the death argument), or the deprivation account regarding death (which I have shortly addressed in the text about the death argument as well in the text about Benatar’s relation to pro-mortalism), two positions that Torres holds, even if for the sake of the argument I’ll ignore my opposition, I can’t see how sacrificing three generations of people can be balanced by the harm to the last generation, especially considering that according to Torres, coming into existence is always a harm, and that death is almost always bad. If so, how is it plausible to condemn more people to the harm of being created and to the supposed harm of death for the sake of preventing only the harm of death from much less people by making them immortal?

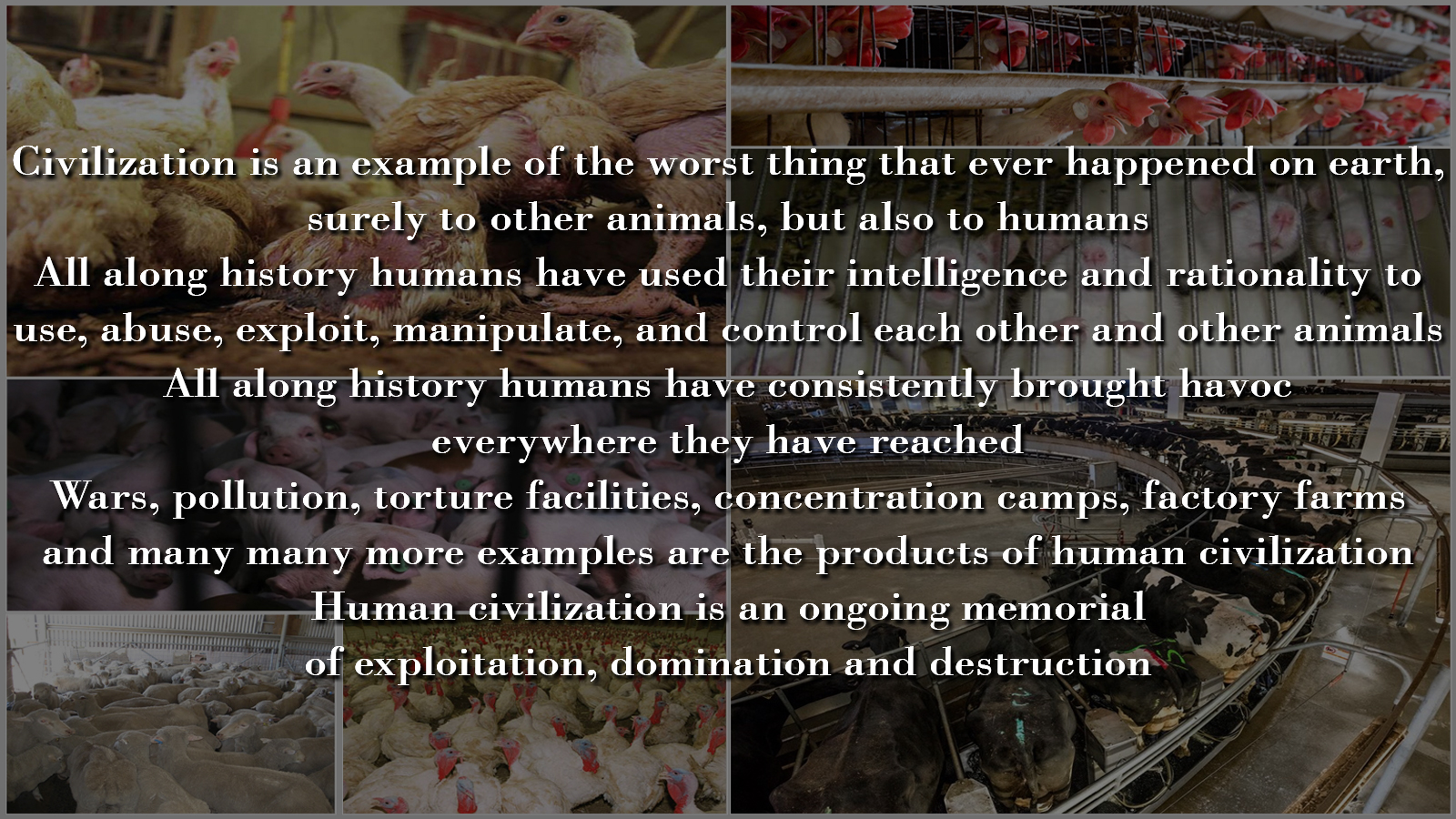

Furthermore, Torres suggests that we ought to weigh the harm of the people from the last generation against the harm of procreation of the people who will need to be created until AEV, but that is a false equivalency. Procreation is not only forcing needless and pointless suffering on the created person, but is also, and in fact first and foremost, forcing needless and pointless suffering on thousands of other sentient creatures, since each person created is hurting thousands of sentient creatures during a lifetime, simply by eating, drinking, cooking, dressing, cleaning, cooling, heating, lighting up, dwelling, moving around, entertaining oneself, and etc.

Considering that every year about 150 billion sentient creatures are tortured in the most appalling ways in the food industry, and considering that that is only part of the suffering humans are constantly causing to others, practically by everything they do, then the suffering of the last generation of people can be balanced, at least in terms of the number of victims, by about two weeks in this hellhole.

Considering the harm to others caused by these three generations, not to mention for eternity, or at least for as long as humanity’s functional immortality lasts, the number of victims, and the extent of their suffering, completely dwarfs the suffering of the last generation.

I don’t at all take lightly the suffering of the last generation, I just fail to understand why it is more important than any other suffering, or how can it seriously be balanced with all the suffering that would be caused to the generations preceding it, all the suffering that all the preceding generations would cause to others, and all the suffering that the last generation would cause, especially if it would gain functional immortality.

And I think that there are ways to significantly ease the suffering of the last generation. Advocating for the right to die for example, if successful, can ease the suffering of many members of the last generation. If these people would have a relatively easy, simple, available, painless way to end their existence, I have no doubt that many would choose it and would spare themselves a lot of suffering involved with getting old.

Or more relevant to this issue, if all the resources needed for functional immortality to succeed would be directed at easing the suffering of the last generation, for example, by providing anti-ageing treatments to several representatives from each community, who would volunteer to ensure a ‘graceful exit’ for the rest of humanity, that can significantly reduce the suffering of the last generation of people. Each community can choose a group of people who would be responsible for the needs of the whole community, and to ensure that these people could indeed take care of the rest, they and only they would receive some treatment, only to ensure as far as possible that they would remain highly functional for another decade or so, and then would gradually perish like the rest.

Torres doesn’t speculate or even mention anything of this sort and I think it is not accidental. I suspect that way more than that Torres is interested in ways to save the last generation, he is interested in “saving” the species. Otherwise he wouldn’t have specified arguments against human extinction, but mainly emphasis that antinatalism has a problem and it is the suffering of the last generation.

But even if it was really the harm to the last generation that was in the center of concern in this article, not only the interests of this generation must be considered, but also the interests of everyone who would be sacrificed and otherwise harmed by this generation. We must consider their interests not to be imprisoned for their entire lives. We must consider their interests not to live without their family for their entire lives. We must consider their interests not to suffer chronic pain and maladies. We must consider their interests not to be deprived of breathing clean air, walking on grass, bathing in water, and eating their natural food. We must consider their interests not to be violently murdered so people could consume their bodies. We must consider their interests that their habitats won’t be destroyed, and that their land, water, and air won’t be constantly polluted.

How many miserable lives does it take for the continence of the human species to become ethically unjustified?

But it goes even further than that. What should be weighed against the interests of people from the last generation is not only the harm of procreation of the at least three generations until the point that functional immortality is possible, and not only the nonhuman animals who would be harmed by these at least three generations, but all the harms, and all the misery, and all the suffering that would ever be caused by humans if they won’t go extinct. The equation is between one generation of people, and all the victims of all the procreations that would ever occur.

The number of individuals who would have to endure all kinds of harms in the future if humans won’t go extinct, is practically infinite.

Objecting human extinction is forcing endless suffering on an endless number of individuals. Harm is unavoidable, the question is of extent. The harm of human extinction is for one generation only. The harm involved in the refusal for human extinction can last for as long as functional immortality lasts.

Even if Torres succeeded in finding a loophole that enables him to remain antinatalist while being anti-extinctionist, he doesn’t succeed in formulating an argument that enables him to remain ethical and anti-specieist while being anti-extinctionist.

The suffering of the last generation can’t serve as an excuse against human extinction. The human race must go extinct because there never was a species even remotely as harmful as humanity. But there can be a worse one and that is an immortal version of humanity. With many more years to live and with many more capabilities, there is no limit to how harmful humans can be in the future.

Digitizing the Problem

Earlier, I have mentioned, only by its title, the first main way to achieve functional immortality that Torres details. Now it’s time to elaborate.

Whole-brain emulation, or “mind-uploading,” involves:

“simulating the microstructure of the brain on a computer with sufficient fidelity to reproduce consciousness. This assumes that minds are multiply realizable, by virtue of being “organizational invariants” that arise from systems exhibiting the right functional organization, whatever the physical substrate (Chalmers 1996). If this “can be made to work,” it would constitute “the ultimate life-extension technology,” since uploaded minds “would not be subject to biological senescence” and “backup copies could be created regularly so that you could be re-booted if something bad happened (thus your lifespan would potentially be as long as the universe’s)” (Labrecque 2017, 166). There are three main forms of uploading: (i) destructive uploading (the original brain is destroyed either gradually or instantaneously), (ii) non-destructive uploading (the original brain remains fully intact while a copy is made), and (iii) reconstructive uploading (the original brain dies but the person is recreated based on historical records) (Chalmers 2010; see also Sandberg and Bostrom 2008).

One version of destructive uploading is the “microtome procedure.” This involves freezing a recently deceased brain to liquid nitrogen temperatures, slicing it into small sections, scanning the slices, transferring this information to a computer, and then simulating the brain. A nondestructive option is to scan the brain “from within … using nanobots” that transfer this information via wireless systems to a computer (Kurzweil 2005). A reconstructive option could become possible if, for instance, a future superintelligent machine were to collect enough data about a past person to design a program that instantiates the relevant functional-organizational properties of that person’s brain (Chalmers 2010). This is predicated on a distinction between clinical death and information-theoretic death, where the latter refers to the point at which no information about one’s nervous system is permanently lost (Merkle 2018).” (p. 16)

Some may recognize potential harm as well as contradiction to antinatalism, from these descriptions alone, and ironically Torres himself specifies some further problems involved in these options that contradict antinatalism and also his view on death:

“The most clearly problematic case involves non-destructive uploading, since this would yield two numerically distinct persons who are psychologically continuous with a single original (who continues to exist as one of these beings).

This leads to two issues:

First, if one maintains that persons, in the metaphysical sense, are intrinsically singular, then they cannot be organizational invariants, which means that the uploaded mind would in fact be a different person than the original; hence, non-destructive uploading would not enable one to achieve functional immortality. Why think that selves are intrinsically singular? Consider a case in which you visit a Digital Immorality Clinic. They pump your blood full of wirelessly connected nanobots that cross the blood-brain barrier and map-out the functional organization of your nervous system. This information is sent to a computer placed within a realistic android, similar to those in the TV show West World. You and this copy are later kidnapped and told that either you—the person that walked into the clinic—or your copy—the person that was created in the clinic—will be tortured for 48 hours and then murdered. Let’s say care most about your own well-being. No rational person would then say, “Pick one of us, randomly. We’re the same person, so it doesn’t matter.” To the contrary, someone acting out of prudence should exhort: “Torture the copy!” The idea that persons are singular entities makes sense of this situation.

Second, whether or not the uploaded mind is you, the fact is that post-upload there would exist two rather than just one conscious entity: the original and the functional isomorph. Hence, non-destructive uploading entails the creation of a new person, and since it is always wrong to create new persons, according to anti-natalism, it must always be wrong to non-destructively upload one’s mind. Call this scenario “digital procreation.” Anti-natalists should therefore strongly oppose this form of uploading independent of one’s view of personal identity.

The same goes for reconstructive uploading: even if the functional isomorph is the same person, it would entail the creation of a new conscious being—a new being at T3 based on the informational patterns of a being who existed at T1 but died at T2—which would be wrong. ” (p.24-25)

And about Destructive Uploading he says:

“Consider a piecemeal process whereby each biological neuron in one’s brain is replaced by a functionally isomorphic artificial neuron. Mark Walker (2008) calls this “gradualism,” and it seems intuitively plausible that it would preserve continuity of consciousness from the beginning to the end, at which point the whole brain has been replaced by non-biological matter. If continuity of consciousness is all that is needed to preserve personal identity, then the person at T2 will be the same as at T1. Benatarian anti-natalists should thus applaud this form of uploading, since it would enable the uploaded person to evade death. But if the person at T2 is different than at T1, the situation would be doubly wrong. The reason is that it would entail not only the creation of a new person, which would be bad, but the death of the original person, which would also (usually) be bad. ” (p.25)

And suggests that Destructive Uploading is anti-antinatalist:

“if one accepts the harm-benefit asymmetry, and if death is (usually) bad, then even a low probability that destructive uploading kills the original while creating a new person should be sufficient for anti-natalists to strongly oppose gradualism. ” (p.28)

Torres raises another potential concern and contradiction to antinatalism:

“A related problem concerns the possibility of duplication gestured at by Schneider and Corabi (2014). As they suggest, once a mind M is uploaded, it could easily be duplicated on multiple computers an indefinite number of times. This is orthogonal to the question of whether M would be personally identical to the original; what matters is that before M has been duplicated, the duplicate M’ does not exist, while after M has been duplicated, both M and M’ exist. Call this “duplicative procreation.”” (p.28)

And the hazardous potential of such an option is enormous, even if not malicious. For example, someone may wish to temporarily emulate its own mind a couple of times so to accomplish many more tasks, and when done to terminate these “spurs”. This scenario is disturbing according to Torres for many ethical reasons:

“Since spurs are numerically separate entities, terminating them would be tantamount to murder—a type of “mind crime,” in Bostrom’s (2016) phraseology. Furthermore, as Anders Sandberg (2014) notes, “if ending the identifiable life of [a spur] is a wrong, then it might be possible to produce a large number of wrongs by repeatedly running and deleting instances of an emulation even if the experiences during the run are neutral or identical” (Sandberg 2014, 288). Even more, since creating spurs entails duplicating mind-uploads, anti-natalists should be especially worried about this futuristic scenario obtaining, since it would mean both creating and killing a conscious entity.” (p.28)

And the malicious potential of such an option is simply inapprehensible. It opens the door for so many harms such as military uses, enslavement, sadism, and etc., that their limit is only the human imagination.

In one of the article’s notes Torres briefly mentions some more concerns in other areas such as:

“In brief, general problems include the question of how society will need to be restructured to accommodate people who will never retire and whether people with indefinitely long lives will suffer from crushingly oppressive ennui— especially if, Soren Kierkegaard (1852) speculated, “boredom is the root of all evil.” There are also concerns about overpopulation, associated today with climate change, ecological collapse, and other environmental ills, if humanity continues to procreate without older generations dying off (see Kuhlemann 2018). Yet ceasing to procreate could remove a major source of value for many people; as Larry Temkin (2008) writes, “if the cost of immortality would be a world without infants and children, without regeneration and rejuvenation, it wouldn’t be worth it.” Even more troublesome is the question of who gets to be included and excluded in the final generation? What happens if apocalyptic terrorists, deranged dictators, genocidal madmen, violent psychopaths, and dangerous lone wolves gain access to technologies that could essentially confer eternal life? Consider that, at the behest of Joseph Stalin, “life-extension became a central subject of Soviet medical research” (Medvedev and Aleksandrovich 2006).” (p.43)

And in another note he mentions that attempts to emulate entire nervous systems could themselves pose some serious ethical hazards:

“as Bostrom notes, “before we would get things to work perfectly, we would probably get things to work imperfectly” (Bostrom 2014b). The result could be that imperfectly simulated brains experience moments of truly intense suffering, perhaps in the form of psychotic hallucinations or delusions, grand mal seizures, and so on, before a normal state of consciousness and mentality is established. (Bostrom 2014b).” (p.44)

Yet for some reason, all of that didn’t convince Torres to abandon such a dangerous and problematic option. There are many other concerns, questions, fears and dangers involved with this idea, but the ones he mentioned are more than enough to firmly support human extinction, ironically, partly because of how potentially harmful human technology can be. And what makes it even more ironic is that such a position is coming from someone like Phil Torres, a scholar whose work focuses on existential risks, and who wrote articles about the risks of artificial general intelligence and space colonization, in which he expressed very deep concerns regarding both.

And many concerns, questions, fears and dangers are not directly involved with how potentially harmful human technology can be, but with how harmful human society already is. There is no reason to believe that all, or at least most of the current problems in the world won’t be emulated along with humans’ minds. Why wouldn’t many of them be transferred into the digital world?

There is no reason to believe that functional immortality, by mind-uploading and definitely by biological anti-aging interventions, would end war, exploitation, discrimination, racism, plunder, enslavement, and other atrocities.

Extending humans’ lives won’t solve their problems but would probably extend them, as people would have more time to suffer and to cause suffering to others. Life would remain terrible only that it would be longer. Extending human life may solve the issue of death, but given that people are addicted to life, even when life is utterly terrible, that is not a solution but a punishment, as they would have to live terrible lives for much longer time. Already people are living terrible lives for too long, so forever?!

Humans’ sick motivations won’t disappear when they would become functionally immortal.

Besides explicitly malicious motivations, possibly, other human motivations such as procreation, may not disappear, even when all humans would be digital. It is hard to imagine it now, but we can’t disqualify the chance that humans would still desire and would find a way to procreate despite not having a biological platform. They might find a way to create a digital being which is the combination of the digital emulations of two people, similar to the way biological procreation works. The desire to procreate is not merely biological in the substance sense. The motivations are coming from various areas, mainly the DNA, not from the ovaries and testicles. And even when the substance is no longer biological, it is highly likely that the DNA which would still be working behind the scenes of the digital versions of persons, as it is DNA that has structured their identities in the first place, would still push people to procreate.

And of course, in the case of biological anti-aging interventions, clearly such a pressure would still play a very significant role.

The fact that Torres doesn’t make an ethical dichotomy between the two main ways that functional immortality could be achieved, already indicates a basic failure. Assuming that the biological format would need the world to be quite similar to the current one in terms of food, clothes, transportation, cleanliness, waste production and etc., on the face of it, this option would be much worse than the digital option which would be less needy on the organic level but probably extremely more needy on the energy production level. On the other hand, as earlier mentioned the digital version has practically infinite potential of harm. Anyway there is a big difference which should be noticed when considering the two routes.

Another very important aspect that doesn’t get any attention in the article is socio-economic. Obviously many people, maybe even most, won’t have access or the required finance for any of the methods and so such technologies might cause the already extreme gaps between people to become even bigger. The danger of creating two kinds of humans cannot be disregarded.

There are many more potential dangers but the point is clear. The risk involved with his position is so great that it is not only to perpetuate the tremendous risk already involved with existence, but to add various more risks, some with a catastrophic potential.

And considering all the sentient beings on earth, we unquestionably already live in a catastrophic world.

Torres argues that some case of uploading may be involved with a potential killing of the original person, or in some cases of the emulated person, therefore he thinks that they might be unethical. However, he ignores that procreation, let alone of at least three more generations so to reach “actuarial escape velocity”, is involved not with the potential killing but with certain killing – mass killing. While it is speculative and arguable if some form of brain uploading may truly be considered as killing, the fact that every person kills many others during its life is inarguable. People are killing others on a daily basis, mostly to feed themselves but also to cover themselves, to move from place to place, to heat their houses, to build their houses, and practically through most of the things they consume.

Human extinction means the end of the whole – exploitation, pollution, confinement, mutilation, humiliation, experimentation, enslavement, torture, slaughter, suffocation, plucking, trimming, dehorning, scorching, skinning alive – project that humanity have conducted more or less from its early beginning. All that would be over when they are gone. That’s why positions against human extinction are speciesist and cruel. Human extinction won’t be tragic but wonderful. Considering the tremendous misery that trillions upon trillions would be forced to keep enduring if it won’t happen, then if the human race would succeed in achieving functional immortality, this already nightmarish world would become an immortal nightmare.

References

Torres, Phil. (2020): Can anti-natalists oppose human extinction? The harm-benefit asymmetry, person-uploading, and human enhancement. South African Journal of Philosophy 39 (3):229-245 (2020)

Torres, P., Futures (2017): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.10.004

Torres, Phil. (2017): Space Colonization and Existential Risks: On Why Following the Maxipok Rule Could have Catastrophic Consequences. Working draft: https://goo.gl/rvDdLj.

Torres, Phil. (2017): Facing Disaster: The Great Challenges Framework. Forthcoming in Foresight.

Torres, Phil. (2019): The possibility and risks of artificial general intelligence,

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2019.1604873

Recent Comments