In her book The Risk of a Lifetime Rivka Weinberg explores How, When, and Why Procreation May Be Permissible.

As the headline implies she thinks that procreation is a risk of a lifetime, and as the subheading suggests, it is a permissible risk but under certain conditions.

Since the road she takes to explain How, When, and Why Procreation May Be Permissible goes through various issues which I have already addressed in previous texts, such as her Hazmat Theory Of Parental Responsibility, the Non-Identity Problem, David Benatar’s Quality Of Life Argument, Seana Shiffrin’s consent argument, and Rawls theory of justice, here I’ll focus on the core of her book – the ‘Principles of Procreative Permissibility’.

For a more complete critical observation of the rest of the ideas she addresses in the book, please read the texts I have just referred to.

The Principles of Procreative Permissibility

Despite that the very first sentence of the book is: “Everybody is somebody’s fault” and despite that shortly after she writes:

“It’s mind-blowing, really. Here we are, in our strange and vast universe, living with many unknowns, uncertainties, and difficulties, and what do we do? We decide to create a creature like ourselves, a sentient, conscious person, with full moral status and a future largely unknown except for the fact that the person will be helpless and dependent for a very long time. How odd of us. Who do we think we are, anyway? Where do we get off? When we procreate, what are we doing and why are we doing it? (p. 15)

Her book is not at all an antinatalist one and she doesn’t think life is a predicament. But she also undauntedly rejects the common notion that life is a gift. As opposed to gifts, which are given for free, can be enjoyed or ignored, but very unlikely to harm the recipient, Weinberg argues that life is not free, it can’t be ignored, and it can definitely harm the created. One has to work hard to enjoy life, and if one ignores life, one is likely to suffer, and of course for many created people life is extremely harmful. So life, even when considered good, is not a gift.

But more importantly, life according to her is not a gift, nor a benefit bestowed by parents on their children, because no one needed, wanted or had an interest in being created before it happened, and no one existed in any other form before being created so no one can be benefited by being created. In her own words: “the future person does not have a good or any state at all to improve, benefit, or better until after the procreative act is complete” (p. 20)

She agrees that procreation is not and can’t at all be an action for the sake of the created people, but is an action for the sake of the parents, as the children are not subjects of interests before they are being created, so how can their creation be for their own sake?

So procreation according Weinberg is not a gift, but it’s also not a predicament, it is a risk, a risk of a lifetime that people choose to impose on other people, and necessarily for their own benefit since being created is never in the interests of a person before it exists. And since this is the setting of creating a person, according to her, meaning, basically a selfish action that imposes a lifetime risk on another person, it needs to have a very good reason.

Weinberg suggests that procreation is a risk that can be justified by two principles she calls the ‘Principles of Procreative Permissibility’:

Motivation Restriction: Procreation must be motivated by the desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born.

Procreative Balance: Procreation is permissible only when the risk you impose as a procreator on your children would not be irrational for you to accept as a condition of your own birth (assuming that you will exist), in exchange for the permission to procreate under these risk conditions.

Weinberg uses a Kantian/Rawlsian framework for constructing these principles, explaining that the Kantian framework is suited to questions of procreative permissibility because it emphasizes the treatment of all persons as ends in themselves and stresses the importance of proper motivation. And the Rawlsian framework is particularly useful for questions of procreative permissibility because it is constructed to yield just principles in cases of distributive conflicts of interests and deliberated about under conditions constructed to reduce bias. She is aware that it is not common to think of procreation as a distributive conflict of interest, but argues that it is one:

“prospective parents have an interest in procreating whenever they please, and future children have an interest in excellent birth conditions. These interests are often in conflict. For example, if parents procreate while they are unemployed, their children will bear some of the costs of their parents’ procreative freedom. If we restrict procreative permissibility only to cases where the future children are likely to have extremely secure economic situations, people who cannot offer this to their children will bear the costs of the security of future children (a category that, in this case, will not include their own children).” (p.7)

In the following text I’ll address her first principle, and in the second part I’ll address the second one.

An End To Others Being Means

With heavy reliance on a Kantian ethical framework Weinberg considers the motivation behind procreation and the treatment of all persons as ends in themselves, to be extremely crucial:

“Just as Kantian contractualism emphasizes the importance of being properly motivated, we have determined that proper procreative motivation is crucial to its permissibility. Proper procreative motivation is important because it helps to ensure that we are procreating in ways that are not disrespectful to children or inconsistent with our broadly liberal values of autonomy, respect, and equality. For example, procreating because one wants to engage in the parent-child relationship as a nurturing parent would be an acceptable procreative motive, but procreating to impress the neighbors would be a problematic procreative motive, regardless of outcome, because it does not treat the future child as a person deserving of respect and value in her own right.” (p. 154)

However, there seems to be a basic and fundamental oxymoron with forcing existence on other people and treating them as ends in themselves. While we should, and hopefully can, treat existing others as ends in themselves, creating others without them desiring, needing, wanting, or having any interests in being created, can’t be treating them as ends in themselves, as they didn’t exist before their existence was forced on them. Weinberg totally rejects people’s false statement that they are creating other people to benefit these people, so how is it that it is impossible and logically implausible to create someone for its own benefit but not that it is impossible and logically implausible to create someone as an end in itself?

The fact that these ends are to raise, love, and nurture their child once it is born, doesn’t make them means to the child’s end, or the child to be an end in itself. The desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born, is still the parents’ desire and never the child’s, since before being created there is no child to have any desire.

Treating a child as an end in itself once it is born doesn’t retroactively make the creation of that child an end in itself. The child was still necessarily born for others’ ends.

In order for a person’s creation to truly be for its own end, it is insufficient for the parents to treat their child as an end in itself, nor for that person to find an end of its own to its own existence, but that the answer to the question ‘why was I created?’ be ‘since I had an end X’. Clearly there is no such option since no one has its own ends before existing. The answer is always ‘since my parents had an end X’. A person can absolutely say ‘now that I exist I have an end X’ and it can absolutely be a reason for its existence after being created, but it can’t be a reason for its creation. No matter how many ends a person would find along its existence, the end of its creation will always be its parents’.

Therefore I find it hard to see how procreation can be defended using a Kantian framework since people are never created as ends in themselves but always as means to their parents’ ends. Being created is never needed or desired by the person being created. It is forced on each and every person, always, and necessarily for motives of others. Or if to go back to the first sentence of the book – “Everybody is somebody’s fault”…

The case in point is about creating people, not about how to treat people after creating them was already decided.

It seems that as far as Weinberg goes the instrumentalization bound with creating people can be covered up if their parents intend to treat them as separate and valuable persons in their own right after they were created. Obviously, treating a person as worthy of respect of its own after being created is highly crucial, however it shouldn’t retroactively change the instrumental circumstances of its creation. It is impossible to create someone not as a mean to others’ ends. And no matter how that person would be treated after being created, nothing can retroactively change that fact.

Weinberg mentions along the book some awful motives for procreation, probably as a rhetoric exercise, hoping to put a positive spin on the motivation she claims can make it permissible. But arguing that – creating a person if there is no intention or ability to ensure that the child would feel self-respect, that she is entitled to love and consideration in her own right – is wrong, doesn’t make the opposite right. They both can be wrong, despite one of them being much worse than the other.

I agree that it will be hard for a child to develop basic self-respect if s/he is not treated as worthy of respect, but that is a good reason to treat people as worthy of respect, and not at all a reason to create people in the first place. Furthermore, the risk imposition, the selfishness, the paternalism, the pointlessness, the pain, the frustration, the stress, the boredom, the sickness, the death and the fear of death, are all still there. All that mentioning some horrible reasons to create a person can prove is that there are certainly even worse reasons to create a person than the ones she suggests, but it can’t prove that her reasons are permissible.

If I want to do something that involves someone else, let alone when that person has no interest in that something happening before it does, I must make sure that at least that person will not be harmed by my desirable action. There is no such option when people are creating people. In fact, it is the opposite, we can be sure that all created people will be harmed, and no motivation and intention to raise, love, and nurture them can ensure that they won’t.

In addition, good intentions do not guarantee good performances (wanting to be a respectful and loving parent does not guarantee succeeding in being one), even allegedly succeeding in treating people as separate persons in their own right, and as entitled to respect and being valued for their own sake, doesn’t ensure good outcomes. Awful and unrespectful relationships between parents and children don’t have exclusivity in misery. There are plenty of other causes and reasons for misery, and there are many miserable children of parents who sincerely tried to be as respectful and as loving as possible. It is simply not at all a guaranteed recipe as life throws plenty of shit at people, and parents are absolutely helpless in protecting their children from all of it.

Wrong Motivation

Besides being irrelevant and insufficient when it comes to questions of creating new people, and besides being selfish and instrumental as well, the mere desire for a relationship which is highly, inevitably, and prolongedly – unequal, paternalistic and controlling – is highly questionable.

Doesn’t the fact that most people don’t want to adopt but desire a biological child of their own, arouse suspicion that it might not be merely the desire to raise, love, and nurture a child? Isn’t it obvious that there is another motive here which involves hubris or narcissism, as people seem to insist on seeing their own genes being spread, on creating an extension of themselves, a mini-me, or something of this sort?

And shouldn’t the fact that the few who are willing to adopt, disproportionally prefer a baby and not a grown child (despite knowing that most of the other people who are willing to adopt prefer to adopt a baby as well, so if they will insist on adopting a baby, parentless grown children might never be adopted), set alarm bells ringing regarding people’s real motives as clearly they prefer that the person they supposedly want to raise, love, and nurture would be as little, as dependent and as cute as possible? Isn’t it because the younger and the more dependent their child is the easier the imprinting process would be? Doesn’t it at all involve ensuring that their child would be more likely to love them back and to fill them with a feeling of power and competent (as after all they are supposedly able to take care of all of someone else’s needs, a feeling that is not available for them with bigger and more independent children)? Doesn’t that preference have something to do with them wanting a cute gadget to love, all the more so one that is way more likely to be an extension of themselves than a grown child is expected to be?

Would people create new people if they were born independent, speaking, intellectually equal adults? No way. And that means that at least part of what they desire is an unequal, paternalistic and controlling relationship.

And of course this case is not even of participating in such a relationship but of creating one, all the more so exactly because that’s what it is (again, people would not create independent, speaking, intellectually equal adults).

So even if that was truly the motivation of parents, there is something awfully wrong about it. And unfortunately, usually, the motivation is even worse than the one Weinberg refers to.

I fail to comprehend how a desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born can justify the blunt and unambiguous elements of imposition, selfishness, and instrumentalization, bound with its creation. Elements which Weinberg is well aware of:

“even if the child’s life is good for the child once the child exists, it is still not a benefit to the child to have been procreated. That’s why we cannot easily claim to create a child to further the child’s interests. The child has interests only if the child exists; otherwise we have no real subject for interests at all. Therefore we do not further the child’s interests by bringing it into existence. We must face the fact that we don’t procreate for the sake of our children. We procreate because we want to. Hopefully, we want to because we want to engage in the parent-child relationship as a parent and participate in a family. Thus we come to an understanding of how we may procreate with a justifiable motive. The parental motive seems justifiable because acting on it may satisfy a unique and legitimate interest of existing people and, arguably, may do so in a way that can be respectful of the future child before the child is conceived and beneficial to the child once the child exists.” (p. 39)

If humans have such a strong motivation to express their desire to love and take care of others, why not directing it towards whom who are in real need instead of creating new unnecessary needy people? By that they are adding insult to injury, since they are devoting most of their time, energy and resources to needs that they have unnecessarily created, instead of to the various needs that were already there. So in that sense, creating new people is not only disrespectful towards the created people, as they are created to serve as mediums for the expression of their creators’ desire to love and take care of others, but it is also disrespectful towards existing people in need who are treated as if their need is less important than a created unnecessary need.

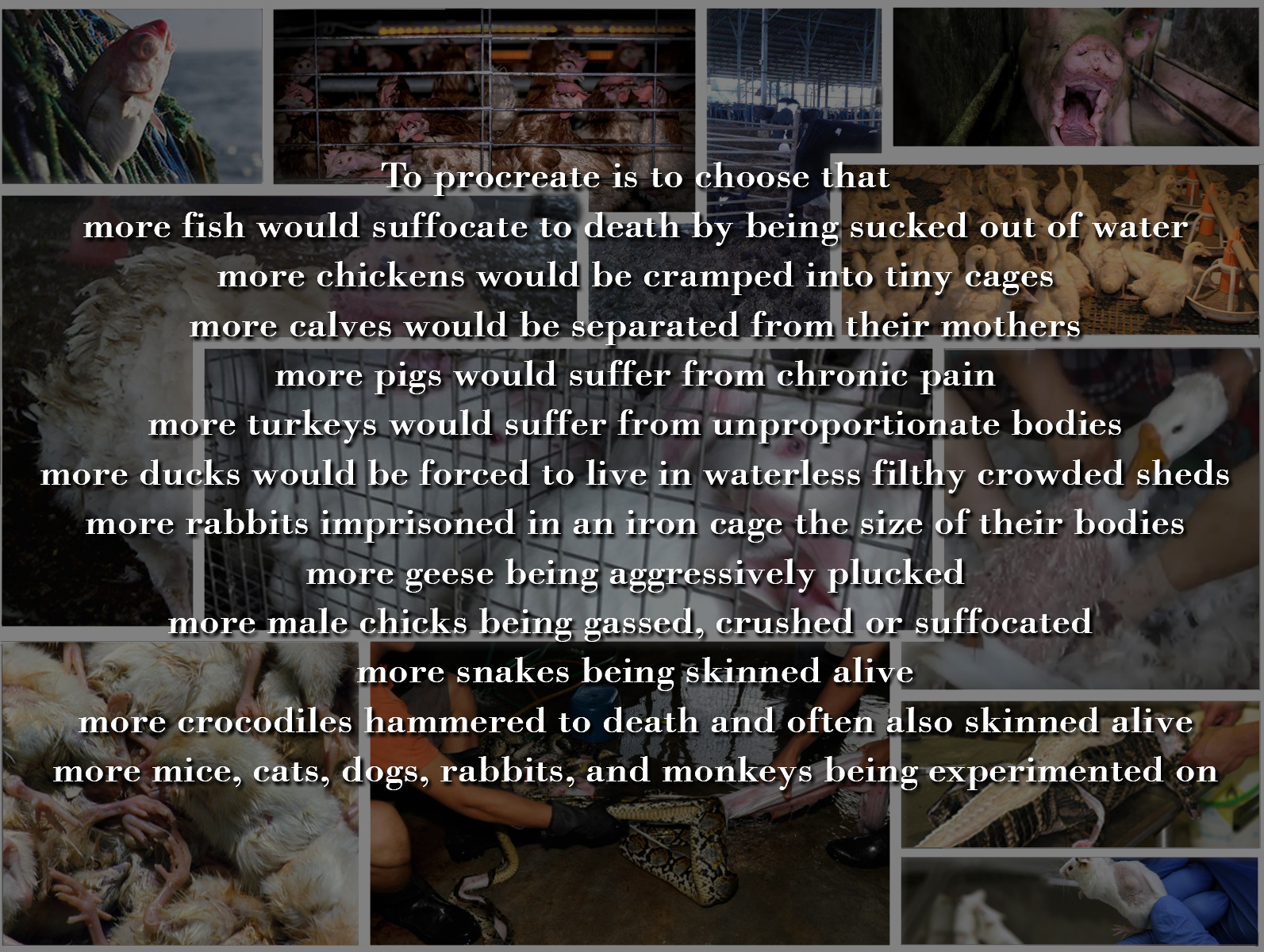

And it all comes with a very high price, imposing unnecessary lifetime risks on others, treating children as means to others’ ends, forsaking people in real need, and creating additional and unnecessary units of suffering, exploitation and pollution.

It is hard to call something a truly and authentically loving relationship when one side is totally depended on the other. The child being absolutely needy and helpless, develops attachment to its parents because they provide vital first aid, mainly through feed and a sense of protection. And that positive association is being formed regardless of any intrinsic quality of the parents. It is not a choice or a preference, but more like a conditioned reflex. This is more like a fixed attachment, an imprinting, than anything authentic.

It is such an unequal, paternalistic and commanding relationship that it needs to be condemned not perpetuated and justified. The fact that it is very common, natural and universal doesn’t make it right.

A structurally unequal and dominating relationship is not justified because these features are natural and inevitable. In fact, since this relationship is naturally and inevitably structurally unequal and dominating, creating it must be avoided.

Procreation involves a dubious motivation and it is wrong to describe it as if it can be a product of a pure desire to raise, love and nurture another person. It is mainly a biological impulse, that can be controlled, is unnecessary, and necessarily has tremendous prices.

Creating a person is creating a biological gadget, even if its creators don’t treat it as one. It is a biological gadget that is supposed to provide its creators love and satisfaction, a sense of power and competence, a purpose for their existence, to ease their existence’s pointlessness, to ease their boredom, to give them a reason to do staff, to recover and maintain their relationship, normalize them in the eyes of society and etc. These motives are rarely openly stated but they are some of the real reasons behind procreation and often behind the motivation to raise, love and nurture one’s child once it is born.

Disrespectful Unequal and Nonautonomous

Having a so called proper motive may be important to ensure that the parents are not disrespectful to their children or inconsistent with broadly liberal values of autonomy, respect, and equality, after the person was created, but it can’t retroactively change the fact that that person was created for its parents’ ends, without equally respecting that person’s autonomy. These values are some of the crucial factors for insuring a respectful treatment of an existing person, but practically they are hardly relevant even for existing children, as they are not really treated as equally respectful autonomous people, and they are not even theoretically relevant for non-existing people.

Unilaterally forcing someone into a relationship which that person can’t really get out of isn’t being respectful of that person. Once existing, a person can’t undo its own existence, undo or change the genetic makeup forced on that person, undo or change the environmental conditions forced on that person, or undo or change the relationships forced on that person.

And there is not even a clean, safe and respectful exit option from any of that, so how is it respectful of the person created?

Suicide, which is not by all means undoing existence, as explained in the text about suicide, is a horrible, harmful, scary and dangerous option. Disconnection from the forced relationship is only optional from a certain age and even then it is always complicated as people are not psychologically built to disassociate from their family, it always comes with a price, and even if it didn’t, it can’t retroactively cancel out the crucial and irreversible effects a family has on a person. Weinberg may wonder why would anyone even want to have these options if its parents really loved and nurtured that person? And maybe most wouldn’t, but some might, and anyway the point is not statistical but fundamental, forcing someone into a situation with no exit options is trapping, not respecting. If there is no respectful exit, how can there be a respectful entrance?

It sure sounds highly disrespectful to create someone to impress the neighbors (one of Weinberg’s examples, which was earlier mentioned), but is it really fundamentally different, in the instrumentalization sense, than the case of procreating because one wants to engage in a parent-child relationship as a nurturing parent? I am not saying it is the same, or that it is equally bad, it is not, but I am wondering how is creating someone as a love and nurture gadget for its parents, so fundamentally and even categorically different than many other selfish motives?

I understand that that person may feel more respected if its parents say that they wanted to raise, love, and nurture a child and not that they wanted to impress the neighbors if are asked why did they create him/her. However, if that person thinks a little bit more deeply about it, the parents wanted to raise, love, and nurture a child, they didn’t want to raise, love, and nurture him/her specifically, and it is them who wanted to raise, love, and nurture a child, not him/her specifically who wanted to be raised, loved and nurtured. So I understand why it feels more respectful than most other reasons, yet I fail to understand why this motive is categorically different.

Impressing the neighbors sounds awfully selfish and instrumental, but a desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born is also selfish and instrumental as in both cases it is not the created person’s need or desire but its parents’. In both cases a person was created unilaterally and according to the parents’ will. The fact that the created person didn’t have a will to consider before being created doesn’t mean that it was nevertheless respected because it will be respected after that person is created. The respect in case should be regarding its creation not its nurture. Respecting someone’s will in existence doesn’t retroactively respect someone’s will in being created, and since there is no will to be created, creating a person can’t be respectful but only forceful.

The desire for a relationship which in its essence is highly unequal and paternalistic, is wrong, and as opposed to her claim it is disrespectful to children and inconsistent with broadly liberal values such as equality, respect and autonomy. Weinberg argues that there are many cases of paternalism that we find justified, but that doesn’t mean that paternalism is unproblematic, only that it is sometimes necessary. It is still a problem and when it is justified it is probably because it is the lesser of two evils. It is justified since without it, someone is going to be harmed. Paternalism towards existing people who lost their ability for autonomy isn’t like creating people who have no ability for autonomy. The fact that we are bound to accept that there are some cases that paternalism is necessary isn’t by any means a justification to create more of it. We need to try and prevent paternalism as much as we can, not justify the creation of more and more of it because sometimes it is necessary. And it is never necessary to create an unnecessary situation which is known to be inherently and inevitably paternalistic.

Some argue that this paternalism is only temporary, but it is for a very long time, it is not at all necessary, and it is not a case of the lesser of two evils for these people. As opposed to the case of paternalism towards existing people, in the case of procreation the choice is not paternalism or harm, as no one is harmed by not being created.

And I disagree that the paternalism is temporary, since by the time the created people become supposedly autonomic they are already deeply designed by their genetic makeup, their surroundings, their so far life experiences (mainly earlier formative experiences), and of course by their parents who usually conduct it all. So how autonomic can a person exactly be when almost everything about that person was predesigned by various crucial factors that determine who that person is and who that person can be, from many aspects. People choose practically nothing of almost each and every crucial factor that has made them who they are, so how can they ever be who they really are? How can they really be autonomous?

There are various elements of coercion in parents-children relationships, there is no option for children to choose until a relatively late stage in their life, and even then these choices are made out of a very particular position which wasn’t chosen by them. The fact that people can’t choose, shape or even influence their own existence conditions including their genetics, their environment, their family, and their early formative experiences makes their creation even more wrong, disrespectful, and inconsistent with broadly liberal values of autonomy, respect, and equality.

Someone’s existence is always a result of an action that doesn’t respect the created person’s independence as a person because consent is never given by that person, the person never chooses anything about its own existence, including the very fact of having one, the person doesn’t have a safe and harmless way of ending its own existence, the person can’t choose its parents, the rest of the family, its neighborhood, its society and etc.

These things are always being selected for everyone. The most affected person never gets to choose anything, and that is always wrong and disrespectful.

Most of the critical things are determined for a person before it becomes an autonomous entity, therefore s/he never really is one in a deeper sense. And that is under the more liberal view, the more inclined you are towards nature in the famous nature vs. nurture debate, the less relevant the autonomy option is. However since no one really chooses one’s environment, it doesn’t really matter whether it is more nature or more nurture, as it is definitely not autonomy. No one really has autonomy over one’s life. No one really freely chooses its own projects, goals, meaning or even its own character.

This is inherent to human life and it is unavoidable. Of course there can be differences, clearly people raised by parents who highly emphasis their autonomy and choice are more likely to become more independent compared with people who were raised by controlling and strict parents. However no parents can avoid controlling their children and highly affecting their autonomy. They are deciding everything for their children, particularly at early ages. They decide for them where they live, they often unilaterally change where they live, they decide what they will wear, what they will eat, what they do, what they don’t do, who to be with, who not to be with and etc. And if parents really want to create autonomous people they must constantly and impartially expose them to an immense variety of options, which is obviously totally unrealistic, and it would only partially deal with only part of the problem which is the environmental effects. It won’t deal with many other environmental effects that parents have absolutely no control over, and it won’t deal with the genetic makeup that no one has chosen but everyone must endure.

Every aspect of children’s lives is controlled by their parents, but what I am mostly bothered with here is not the structured and inherent paternalism but that in many senses people are significantly designed by their parents, and by many other factors which they have not chosen or can retroactively affect. The more profound aspect of non-autonomy is that people don’t get to choose who they are, who they will be, who they can be, who they want to be, their boundaries and etc. This is not a temporary coercion but a lifetime one.

Procreation is creating a person. A person that not only has not chosen to be created, but also has not chosen anything involved with its creation nor most of the most crucial elements in determining who that person is. Procreation is creating a person who is forced to be the carrier of certain genetic makeup, environment, and formative experiences, without any option to really evade their crucial effect, an effect that in one way or another will be part of every choice that person would ever make. Way more than totally controlling their lives until a certain age (as important as it is in itself), that is the profound coercion and non-autonomy that is intrinsically involved in creating a person.

In conclusion, I disagree with Weinberg that this motivation ensures that people are procreating in ways that are respectful to children or consistent with broadly liberal values of autonomy, respect, and equality, or that this motivation is categorically different in the sense of treating children as means to others’ ends. I think that this motivation is nevertheless disrespectful, unequal, non-autonomous, and instrumental.

But even if I agreed with Weinberg, and even if such a motivation could have been genuine (and not extremely problematic, to say the least, and not disrespectful to children, and not inconsistent with broadly liberal values of autonomy, respect, and equality), what does it say about procreation if one of the two principles of procreative permissibility is what should have been the most self-evident reason for procreating? It is awfully sad that people need to be told that they must be motivated by the desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born, and not by any other motivation, when they are planning to create a person.

The fact that she seriously argues that such a motivation must be initial to procreation only strengthens antinatalism as it is supposed to be extremely clear. And the fact that not only is it rarely the motivation, but that usually there is not even a feeling or need to come up with explicit motivations for procreation, or any thought about such a profound and crucial decision whatsoever, makes antinatalism even stronger. It indicates on the ease with which people are imposing risks of a lifetime on other people. And that disrespectful ease means that people are far from being responsible enough in order to put the fate of others in their hands.

If humanity has reached the 21st century and it needs a philosopher to dedicate a whole book to explain people under which circumstances procreation may be permissible, and these would be that they are motivated by the desire and intention to raise, love, and nurture one’s child once it is born, then clearly procreation mustn’t be permissible under any circumstances.

If it needs to be explained methodically and while eliminating unjustified and false motives it means that procreation mostly happens for unjustified and false motives. And if it mostly happens for unjustified and false motives there is a problem with the agents, since it is not that the “justified” and “right” motives are complicated, but rather that they should have been absolutely self-evident. But they are absolutely not. And that is extremely worrying.

If such an obvious factor must not only be mentioned but is one of the two formulated principles, then obviously there is something terribly wrong with the reasons people procreate and have been procreating so far. And if something is so wrong with the reasons people procreate and have been procreating so far, then maybe she doesn’t need to make the effort and formulate principles that can justify it, but conclude that people better never to have breed.

The second part of this text addresses Weinberg’s second principle of procreative permissibility: Procreative Balance

References

Benatar David. Better Never to Have Been (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006)

Shiffrin, S.V. Wrongful life, procreative responsibility, and the significance of harm. 1999

Legal Theory 5: 117–148

Weinberg, Rivka. Existence: who needs it? The non-identity problem and merely possible people

2012 Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702

Weinberg Rivka The Moral Complexity Of Sperm Donation

Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702 (print); 1467-8519 (online) doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00624.x

Volume 22 Number 3 2008 pp 166–178

Weinberg Rivka. The Risk Of A Lifetime (Oxford University Press, 2006)

Recent Comments