In an article called What’s wrong with human extinction? Elizabeth Finneron-Burns addresses the question of whether or not it is morally permissible to cause or allow (by doing nothing to prevent it) human extinction to occur. Put it another way: “under what (if any) conditions would people causing or allowing the extinction of the human race be wrong?”

To answer this question Finneron-Burns examines the four reasons that could be given according to her, against the moral permissibility of human extinction. She considers them from a contractualist perspective, meaning basically that: “We wrong others when we fail to consider their interests in our moral deliberations and do not give them the respect they deserve by virtue of being rational people. This happens when we cannot justify our actions to them using acceptable reasons or when we act according to a principle that they could reject for similarly acceptable reasons.” This perspective is a type of person-affecting theory, meaning that what is important is the effect of principles/actions on persons, rather than ‘the world’. Acceptable reasons for either justifying a principle or rejecting one, must be personal – it must have an impact on a person or persons.

- It would prevent the existence of very many happy people

Many people find it intuitive that we should want more generations to have the opportunity to exist. They claim against human extinction since it deprives more people of something good which is to exist and enjoy happy lives.

However, Finneron-Burns rightly rejects this claim arguing that we can only wrong someone who did, does or will actually exist.

A possible person is not disadvantaged by not being created. In order to be disadvantaged, there must be some detrimental effect on a person’s interests. However, without existence, a person does not have any interests so they cannot be disadvantaged by being kept out of existence, “a principle that results in some possible people never becoming actual does not impose any costs on those ‘people’ because nobody is disadvantaged by not coming into existence.” (p.6)

No one acts wrongly when they don’t create another person, and hence if everybody decides not to create new people – which would eventually lead to human extinction – it is also not wrong.

Some might disagree, arguing that human extinction is a loss of positive value. However, under the contractualist perspective that Finneron-Burns uses in this article, something cannot be wrong unless there is an impact on a person. Therefore she concludes that “neither the impersonal value of creating a particular person nor the impersonal value of human life writ large could on its own provide a reason for rejecting a principle permitting human extinction.” (p.7)

- It would mean the loss of the only known form of intelligent life and all civilization and intellectual progress would be lost

Many people claim that human extinction would be a terrible loss since humans are the only known intelligent, rational and civilized life.

As in the case of the first argument, Finneron-Burns also rejects this one for being impersonal.

Since the loss of intelligent, rational and civilized life would impact no one’s well-being or interests, it is not wrong.

She also quotes Henry Sidgwick who claimed that these things are only important insofar as they are important to humans. “If there is no form of intelligent life in the future, who would there be to lament its loss since intelligent life is the only form of life capable of appreciating intelligence? Similarly, if there is no one with the rational capacity to appreciate historic monuments and civil progress, who would there be to be negatively affected or even notice the loss?” (p.8)

Although I agree with the counter argument she presents, I think it’s unnecessary as the premises of the argument it counters are false. Humans are far from being the only intelligent and rational beings in the universe, and I am not basing this claim on encounters I’ve had with extra-terrestrials but with nonhuman animals here on earth. I don’t think that the loss of intelligent and rational life is by itself a valid reason against extinction, but even if it was, since humanity has no exclusiveness on either, to claim against extinction because of the loss of intelligence and rationality is definitely not valid.

On the other hand, human intelligence and rationality is definitely a valid and sufficient argument for human extinction. All along history humans have used their intelligence and rationality to use, abuse, exploit, manipulate, and control each other, and other animals.

All along history humans have consistently brought havoc everywhere they have reached.

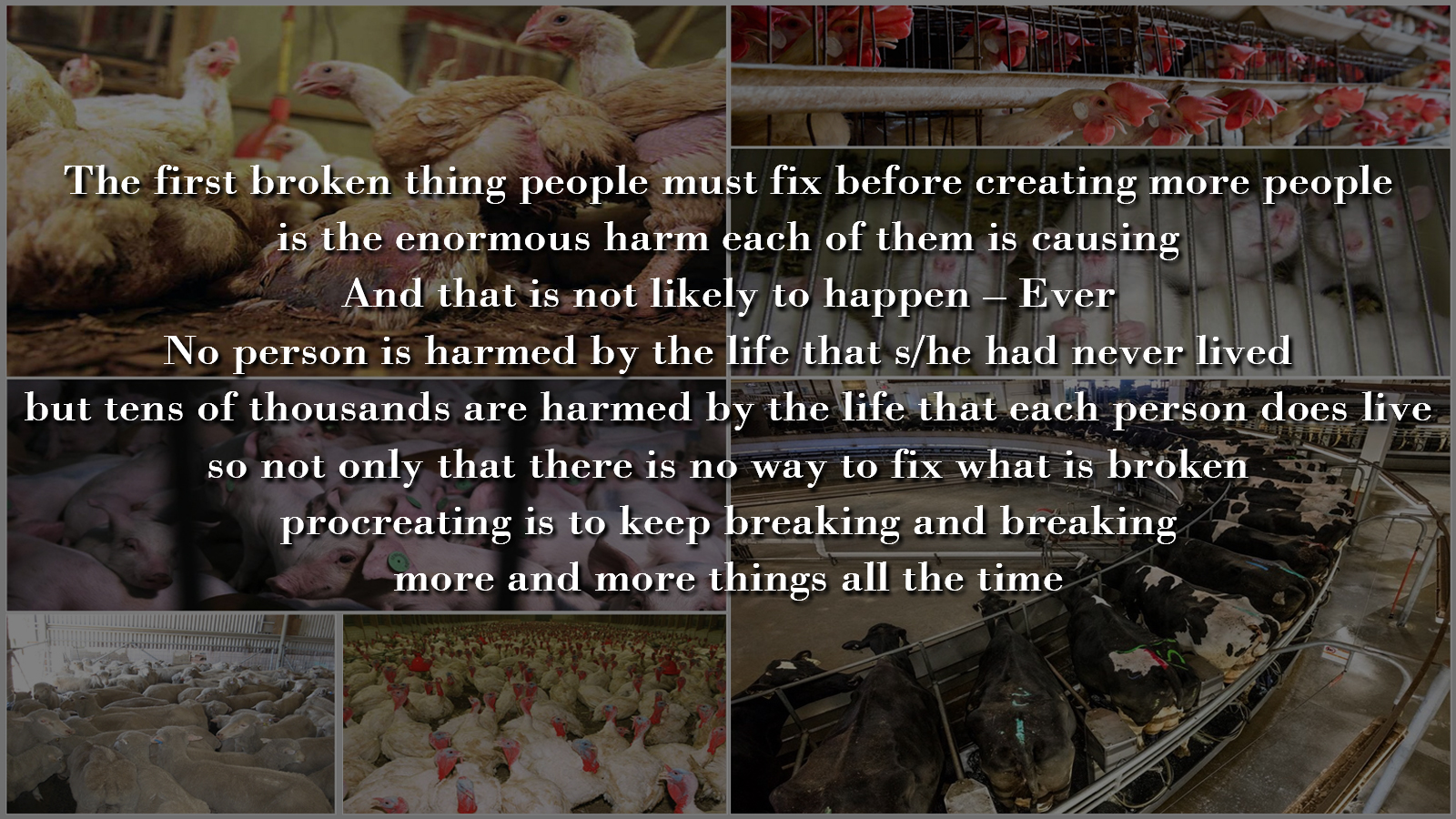

Wars, pollution, torture facilities, concertation camps, factory farms and many many more examples, are the products of human civilization and intelligence.

Human civilization is an ongoing memorial of exploitation, domination and destruction.

Human extinction is not a loss but a benefit. A benefit to probably tens of millions of humans whose lives are extremely miserable, and surely to everyone who isn’t human.

- Existing people would endure physical pain and/or painful and/or premature deaths

Basically this claim is that since it seems uncontroversial that the infliction of physical pain could be a reason to reject a principle, and since the ways in which human extinction might come about might involve significant physical and/or non-physical harms to existing people and their interests, extinction is wrong.

With this argument Finneron-Burns agrees. She also presents a counter argument to this claim, and then explains why it is wrong:

“Of course the mere fact that a principle causes involuntary physical harm or premature death is not sufficient to declare that the principle is rejectable – there might be countervailing reasons. In the case of extinction, what countervailing reasons might be offered in favour of the involuntary physical pain/death-inducing harm? One such reason that might be offered is that humans are a harm to the natural environment and that the world might be a better place if there were no humans in it. It could be that humans might rightfully be considered an all-things-considered hindrance to the world rather than a benefit to it given the fact that we have been largely responsible for the extinction of many species, pollution and, most recently, climate change which have all negatively affected the natural environment in ways we are only just beginning to understand. Thus, the fact that human extinction would improve the natural environment (or at least prevent it from degrading further), is a countervailing reason in favour of extinction to be weighed against the reasons held by humans who would experience physical pain or premature death. However, the good of the environment as described above is by definition not a personal reason. Just like the loss of rational life and civilization, therefore, it cannot be a reason on its own when determining what is wrong and countervail the strong personal reasons to avoid pain/death that is held by the people who would suffer from it. Every person existing at the time of the extinction would have a reason to reject that principle on the grounds of the physical pain they are being forced to endure against their will that could not be countervailed by impersonal considerations such as the negative impact humans may have on the earth.” (p.11)

Finneron-Burns’s rejection to the counter argument she presents is utterly wrong because it falsely switches the personal interests of trillions of sentient creatures with a non-entity abstract concept such as ‘the natural environment’.

But the case is not of humans being a harm to ‘the natural environment’ but of humans being a harm to trillions of individual sentient creatures. It is not a case of the impersonal environment which is weighted against existing persons, but trillions of existing sentient individuals weighted against existing people.

She is making such a false presentation of the situation in her premises so she could later conclude that the counter argument is impersonal, but it is not that “the world might be a better place if there were no humans in it”, but that the lives of trillions of persons would be better if there were no humans in it. It is not the fact that human extinction “would improve the natural environment”, but that it would improve the lives of other sentient creatures. Her rejection to the counter argument speciesistly nulls the interests of trillions of sentient creatures treating them as if they are an abstract concept and not individuals entitled with moral consideration.

Only because she falsely describes the harms to trillions of sentient creatures as a harm to the environment, Finneron-Burns can claim that this argument fails since it is impersonal. Obviously ‘the environment’ is not a moral entity as it has no interests. But the sentient creatures who live in the environment are moral entities, it is them who have interests we all must consider. When using a correct description, this argument is valid, firm and unequivocal. Human extinction would probably be consensually decided upon by all sentient creatures had their interests been considered.

But they are not. Trillions of existing sentient individuals matter so little to humans that even when they are allegedly being given as reason for human extinction, they are diminished to an impersonal reason. Instead of being trillions of strong independent reasons for human extinction, they are presented as one weak impersonal reason. That is human chauvinism. It is speciesism.

For humans to live, nonhumans suffer and die by the billions all the time. Human life has no value of its own outside of human life, and human life is not more important to humans than the lives of nonhumans are important to nonhumans. Thinking otherwise is speciesism.

Moreover, the harm humans inflict on other sentient creatures is so vast that practically there is no human action in modern society that doesn’t harm an individual, an animal person, somewhere in the world. Humans don’t harm the environment as there is no such option. The environment is not a moral entity. It is not sentient and it has no interests. The harm is inflicted on sentient creatures. The fact that these creatures are totally meaningless in humanity’s view, doesn’t serve as a justification to null each of these animal persons and turn them into an impersonal reason. They are all persons. They view themselves as persons just as the humans who harm them view themselves as persons. Only that no one considers their personal interests. To keep considering humans’ procreation interests means to keep ignoring all the interests of all the other creatures. And that’s why we should stop considering the personal interests of humans to procreate.

‘The good of the environment’ may not be a personal reason, but the good of each of its inhabitants, is. Unlike the loss of rational life and civilization, it can be a reason on its own when determining what is wrong with human extinction, and if we ask all of the inhabitants it would probably be that the only thing wrong with human extinction is that it didn’t already happen.

- Existing people could endure non-physical harms

The final reason against human extinction Finneron-Burns discusses is the psychological effects that might be endured by existing people who are aware that there would be no future generations.

One psychological effect she mentions is the negative effect on well-being that would be experienced by those who would have wanted to have children. “Reproducing is a widely held desire and the joys of parenthood are ones that many people wish to experience. For these people knowing that they would not have descendants could create a sense of despair and pointlessness of life.”

And she adds that “the inability to reproduce and have your own children because of a principle/policy that prevents you would be a significant infringement of what we consider to be a basic right to control what happens to your body.” (p.11)

As in the case of the third argument, Finneron-Burns agrees with this claim, and as in that case I think her agreement is wrong. In fact, in a way, supporting this argument is even worse, since it implies that because people would never voluntarily do the right thing and not procreate, it is morally permissible for them to procreate, and it is morally impermissible to force them not to.

fcoSince antinatalism necessarily entails human extinction, as obviously if everyone apply its ethical rule eventually the human race would go extinct, when arguing against human extinction, one must also counter antinatalism, as obviously the practical opposition to human extinction is procreation.

So among other things, to counter claims for human extinction, Finneron-Burns should argue that procreation is not a crime, not that people would be hurt if they are not allowed to commit that crime. Antinatalists know that people want to create new people, that’s why they are arguing against it. Had people not wanted to procreate there would have been no need for no arguments.

Lets’ take for example one of the most popular antinatalist arguments – the consent argument – which goes more or less like this: Causing harm to another person is morally justified only if that person had provided an informed consent, or in the case an informed consent cannot be provided but causing harm is in the best interest of that person since otherwise a greater harm would be caused to that person. Some also add the case of causing harm as a punishment for a crime. Since forcing people into existence is subjecting them to harms without their consent, and without it being in their best interest (for the obvious reason that before its existence a person has no interests, as there is no person), and it is also definitely not the case of punishment for a crime, procreation is morally impermissible.

Arguing that ‘reproducing is a widely held desire and the joys of parenthood are ones that many people wish to experience’ is not an admissible reply to the consent argument. It can’t serve as a counter argument to the consent based argument for antinatalism which obviously, as all antinatalist arguments, entails human extinction.

So for that matter, Finneron-Burns should have argued against the consent argument, not explain that people would be hurt if they can’t procreate because they want to, or at least try to explain how is it that the interests of the prospective parents subdue the interests of the potential child.

The question in point is ‘is it morally permissible to stop people from doing what they want’. And so the answer can’t be ‘no’ because they don’t want to stop.

If it is a valid reply then it should be valid in other cases of causing harms to others just as much. And then, all that any offender should claim is that by stopping him from committing a crime we are making him the victim. And that would be to nullify criminalness. Every offender would be hurt if they couldn’t continue with their offences, is it a justified reason to let them go on with their offences?

What is often called crimes of passion are not permissible since the offender would be hurt had s/he not committed the crime.

Rapists might feel hurt if they are not allowed to rape, or if they are caught, is that a reason not to do everything we can to stop them? Can the desire to rape be an argument in favor of raping?

Obviously people want to procreate, that’s why they refuse to stop, but that is a description of our dire reality, not an ethical justification of it.

Can people’s desire to eat animals be a justification for the torture which is factory farming?

Arguing that all factory farms must be closed down today for the pain and misery they cause can’t be seriously counter argued by claiming that people have a desire to eat meat, eggs and milk. Some might argue that eating meat is not like creating new people, but I fail to see the fundamental difference in this context as in both cases people do as they please at the expense of others without their consent.

The argument that since humans would suffer from fixing the dire situation they themselves have created (and refuse to fix by themselves), we are not allowed to fix it without their consent, is wrong. They keep intensifying the problem by creating more and more of them, with no consent from the ones they are creating, nor from the ones who are hurt by the ones they are creating, so why is it that the solution to the problem must be with their consent?

And don’t get this wrong, I am not suggesting it as a punishment or anything of this sort, but only to stop the crime, and the suffering caused by each procreation.

The second psychological effect Finneron-Burns mentions is a sense of hopelessness or despair that people would feel knowing that there will be no more humans and that their projects will end with them:

“Many of the projects and goals we work towards during our lifetime are also at least partly future-oriented. Why bother continuing the search for a cure for cancer if either it will not be found within humans’ lifetime, and/or there will be no future people to benefit from it once it is found?” (p.12)

First of all, despite that her specific example is obviously not the main issue, it is hard not to comment on the “Why bother continuing the search for a cure for cancer”, since it is so manipulative. There are currently about 8 billion people on earth, probably only a couple of thousands of them are searching for a cure for cancer, while many more are busy causing it, to themselves, to their children, to other people, and to other animals. Most people are not searching for any cure to any disease or any solution to any other problem, but live their selfish pointless little lives. They were born for no reason other than the desire of their parents, and certainly not so they can search for a cure for cancer, and they are forcing new people into life for no reason other than their desire, and certainly not so that their children would search for a cure for cancer or anything even remotely close.

What happened to Henry Sidgwick’s claim that things are only important insofar as they are important to humans? If there is no one who suffers from cancer, who would there be to lament the loss of searching for a cure? This example is awful since it is supposed to be good that there would be no longer a need to search for a cure for cancer. With no cancer patients there is no need to cure it. How can the existence of such a horrible disease serve as the basis for an example against human extinction? Searching for a cure for cancer is good only if there are existing people, and if some of them suffer from it. If there are no cancer patients then the problem is solved, not created.

And by the way, there would be cancer patients in the case of human extinction – nonhuman animals. Why not searching for a cure for them? Or at least ways to prevent some of the cases from affecting them, for example by searching for the least harmful ways to dismantle all the nuclear weapons and nuclear power stations before humans go extinct and animals suffer the consequences? Why? Because humans don’t care.

But much more important than her specific example, is her claim. Arguing that human extinction is wrong since existing humans would lose interest and meaning in their lives, is in my view like suggesting that people should force new people into existence to bestow their own lives with interest and meaning. Of course most procreations already are a result of people bestowing their own lives with interest and meaning, but this real reason is usually concealed by the fallacious proclaimed reason which is to bestow interest and meaning to the future child. Finneron-Burns on the other hand, suggests this claim as a moral justification for doing so. It’s using someone as a mean to others’ end, and it is wrong. Imposing lifelong vulnerability on someone, without consent, and with a certainty of harming others, so that the creators of that person would have interest and meaning in their lives, is not only wrong, it is cruel.

Conclusion

Examining the four reasons she suggests that could be the basis for reasonably rejecting principles permitting human extinction, Finneron-Burns rejects the first two which are:

(a) It would prevent many billions of happy people from being born.

(b) It would mean the loss of the only form of intelligent life and all civilization and intellectual progress would be lost.

And accepts the other two which are:

(c) Existing people would endure physical pain and/or painful and premature deaths.

(d) Existing people would endure psychological traumas such as depression and the loss of meaning in their pursuits and projects.

Probably the saddest thing about this article is that despite all its flaws, most claims regrading human extinction are even worse. Most people are against human extinction for all four reasons, and especially the first two. These claims are not only extremely speciesist as the latter two are, but are also entirely human chauvinist, as they see a value only in the human race’s existence, and no value in the world (inhabited with other sentient creatures) without it.

I agree with the claim that the human race has a tremendous value, only that it is a negative one.

The human race is with no proportion the greatest wrongdoer in history. And things are not getting better. And even if they were, they are currently so horrible that the harms to existing humans is marginal compared with the harms to existing nonhumans, which quantitatively speaking already by far exceeds the number of existing humans, not to mention when considering the harms to every nonhuman who would ever be born. There are more nonhuman animals in factory farms at any given moment than there are humans on this planet. For their sake alone human extinction is utterly justified. The harm to existing people by preventing them from procreating, can’t seriously countervail the harms to generations upon generations of sentient creatures whose suffering would be prevented in the case of human extinction.

The question in point shouldn’t be what’s wrong with human extinction but what’s right with human extinction. And the answer is that it depends on who we ask. If we keep asking humans only, then the answer of most would be there is nothing right about human extinction, and only a tiny minority would argue differently. But if we ask anyone who would be affected by human extinction, anyone whom this question is relevant for but is never asked, an absolute majority would unhesitatingly say that what is right with human extinction is everything.

References

Elizabeth Finneron-Burns: What’s wrong with human extinction? (Canadian Journal of Philosophy 2017)

Recent Comments