Procreation is always wrong no matter who is procreating, including considerate people such as ethical vegans who plan to raise their children to also be considerate people and ethical vegans. When these kind of people are procreating it is not necessarily as bad as when others are procreating since it is more likely that when the parents are considerate people such as ethical vegans, their children would be so too and therefore their toll on others in terms of harms would be smaller than when the parents are selfish, carnivore, consumerist assholes. However when ethical vegans are procreating it is much more disappointing, and more importantly it serves as proof for the known in advance failure of voluntary antinatalism.

Double Standard

Many ethical vegans are furious when antinatalists criticize them for procreating or for planning to procreate, claiming that it is their choice. That is a clear case of double standard since when non-vegans are telling vegans to stay out of their plate, the ethical vegans, absolutely rightly, reply that it is them the non-vegans who insist on imposing suffering on someone else in order to satisfy their own needless selfish desires, but when antinatalists tell ethical vegans who plan to procreate, that procreation is wrong, they usually tell the antinatalists to stay out of their ovaries. That is despite that procreation is also a case of imposing unnecessary suffering on someone else without consent. Non-vegans are not staying out of someone else’s life and therefore it is absolutely justified not to ‘stay out of their plate’. And since ethical vegans who are planning to procreate are not staying out of someone else’s life, it is absolutely justified to not ‘stay out of their ovaries’. Just as it is not a personal choice to harm others by eating them, it is not a personal choice to harm others by creating them.

And more importantly, since vegans also severely harm others in many ways, such as poisoning, trampling or chopping with agricultural equipment, trapping, shooting, destructing their habitat, polluting their air, polluting their water, stealing their water, stealing their food, dividing their homes, placing fences in their homes, illuminating their nights, making constant disturbing noises in what used to be their silent environment, and so on; creating a person, even if it was possible to absolutely guarantee would remain vegan for life, is not a personal choice too.

Vegans despise the claim that the meat industry actually benefits animals since it allegedly provides them with food, water and shelter from harsh weather, as well as protection from predators. Obviously there are some fundamental differences between the cases, yet vegan parents often sound exactly like the “argument” they hate so much, claiming that their children would have good lives despite that at least some pains and difficulties which none of the children have consented to endure are certain. Although vegan parents are not creating their children for profit and they will not murder them at a certain point, they do create them for their own personal benefit and not for the benefit of the children who didn’t need nor wanted anything before they were forced to exist. And all parents do condemn their children to die. Most children won’t be murdered, and definitely not by their parents, but they will die and will be aware of that for most of their lives. They wouldn’t have to die, or suffer from being aware that they have to die, had their parents not created them.

There are definitely differences between breeding animals and breeding people, but there are also some troubling similarities, which ethical vegans of all people should be the last ones to ignore them.

Ethical vegans absolutely rightly oppose breeding of “companion animals”, especially since there are so many homeless ones. I disagree with the adoption argument for antinatalism, mainly since it is antinatalism on condition while procreation is always wrong regardless of the number of children who are waiting for adoption. And the same goes for animal breeding, it is always wrong to breed an animal, regardless of the number of animals waiting for adoption. However, obviously in both cases, the fact that there are so many existing creatures who need a home makes procreation an even greater crime. Ethical vegans agree with this claim when it comes to animals but for some reason the ones who support procreation, don’t apply it to humans. There is no reason why breeding animals to be used as human companion while there are so many abandoned ones who are doomed to a lonely and miserable life in the pound, is morally wrong, while breeding humans to be used as human companion, to take care of them when they are old, to save their decaying relationships, to continue the family line, to fill their empty and pointless lives with a sense of meaning and purpose, to feel powerful because someone is totally depended on them, to feel needed and important, to hush their biological impulses, to boost their ego, to create an immortality illusion, and etc., is not morally wrong just as much.

Most ethical vegans support spay and neuter for animals whose offspring might otherwise be left homeless, abandoned, run over in the streets, suffer from cold, heat, hunger, thirst, abuse, fear, loneliness, or if caught, to live in a cage inside a pound. When it comes to these animals, they don’t argue that it is natural for them to breed, or that we must stay out of their ovaries, or that it is their right and choice to breed and etc., well, human breeding is responsible for much much more harms than animals breeding. Although in the case of cats and dogs they should be spayed and neutered for the sake of cats and dogs (who would otherwise be born into a life of misery), and in the case of humans they must be spayed and neutered mostly for the sake of all the creatures who would be hurt by their offspring, that difference is not the reason for the different stands pro-natalist ethical vegans hold. They support spay and neuter in the case of animals but not in the case humans simply because they themselves want to procreate. Other vegans might oppose spay and neuter for humanity regardless of their desire (or lack of it) to procreate, and that might simply be because they are speciesist.

When pro-natalist ethical vegans are asked what if your children would choose to consume animals someday? many reply that they would do everything they can to prevent that, but ultimately, it would be their children’s choice. But they don’t think that it is the choice of non-vegan strangers whether to harm others or not. So, when it is non-vegan strangers they don’t think it is their choice but when it comes to their children it is not only their choice but the option to harm others was given by them. Had they not procreated at least the harm that their children are causing would have been avoided.

But it is more than the double standard issue, the expectations from ethical vegans are much higher, in general, and especially since they know all too well the opposite stand. They know best how frustrating it is that despite that they are advocating for such a rational, right, and morally self-evident decision such as veganism, they encounter again and again and again walls of ignorance and stupidity. Unfortunately many of them act similarly when it comes to their desire to procreate.

Double Risk

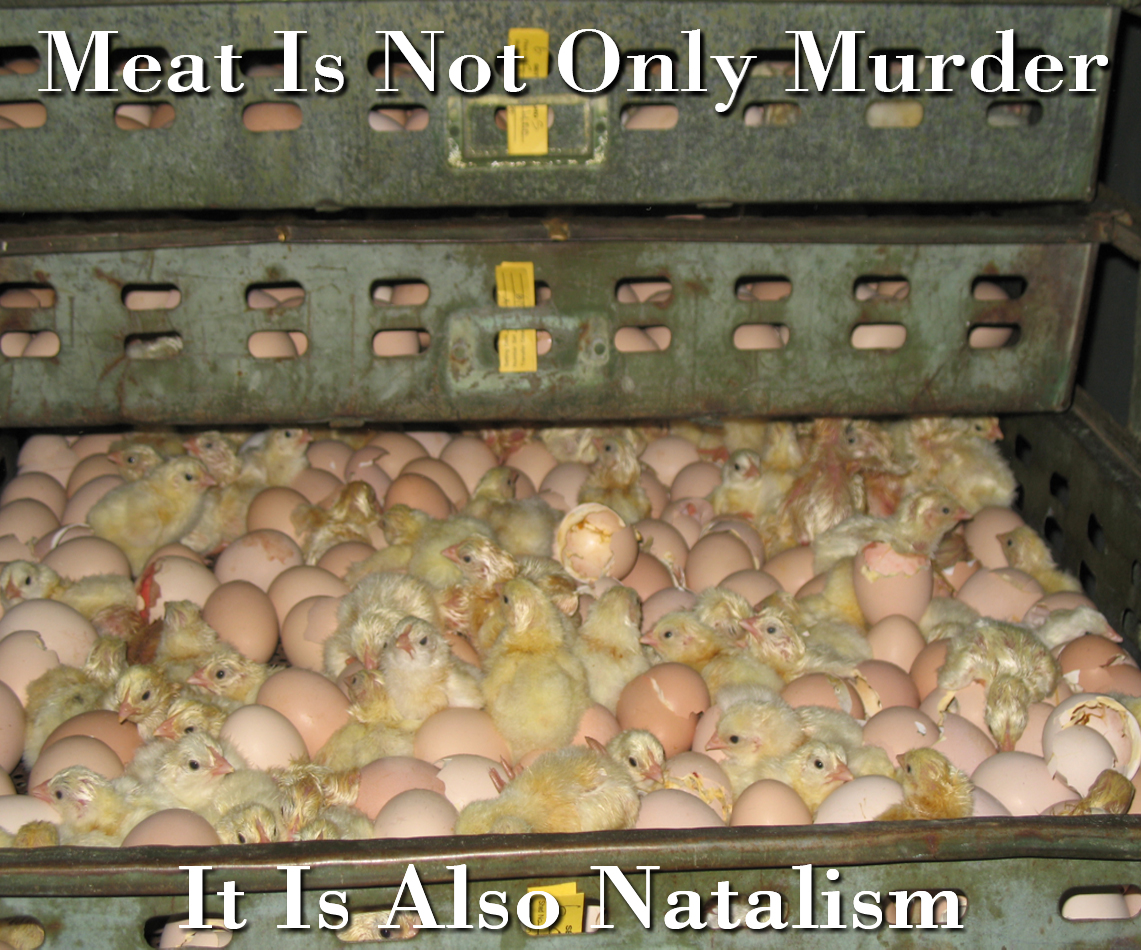

It is always wrong to procreate since it is taking a risk with someone else’s life. In the case of ethical vegans there is another risk which is that their children won’t stay vegans for the rest of their lives. Many ethical vegans are not deterred by that option, claiming that their children would surely be vegans for the rest of their lives, despite that there is absolutely no guarantee for that. Many children choose different paths despite their parents’ best efforts. In fact there are many vegan parents whose children stop being vegan when they grow up, and sometimes at a very early age. Many children are exposed to non-vegan food when they first go to kindergarten, pre-school, play dates, others’ birthdays and etc., and that is when many want to stop being vegan. There are some cases of separated parents where the children are vegans when they are with the vegan parent and non-vegan when they are not. So not only that it is wrong to put animals at risk by creating a new person with no guarantee that that person would be vegan for life, there are already many cases of vegan parents to non-vegan children. So it is not only wrong in principle, it is already factually based that children of vegan parents don’t necessarily stay vegan themselves. There is even a Facebook page devoted to such cases called Vegan Army Failures, where you can see posts made by vegan parents whose children stopped being vegan.

And it is not only the children who must be vegans for life to allegedly justify procreation, it is also the children’s children, and their children, and so forth. Can every vegan guarantee that all his future offspring would be vegan for life? Of course not. There is no way to control every future decision and action one’s children would ever make. Not to mention their children’s children. If only 2 of them decide not to stay vegan that’s already more harm than was reduced by the original parents being vegans. And in the worst case, vegans’ children might create a long line of meat eaters who breed more and more meat eaters.

Ethical vegans who procreate would never ever consider consuming animal based products. But it is possible that their children would someday have different values and perspective and so decide to consume animal based products. In such a case, in terms of net harm, the ethical vegans’ decision to procreate nullifies their veganism. As counter intuitive and crazy as it may sound, it is better that they themselves would stop being vegan than procreate. That is of course not a suggestion nor an implication that it is more important not to procreate than it is to go vegan, as there is no need to choose, obviously there is no contradiction between the two. In fact these are two of the most basic moral decisions anyone must make. The point is that procreation is so risky and harmful that it might end up being worse than not going vegan.

And even if that gamble would turn out successful and all the offspring would stay vegan for life, veganism is still causing an enormous harm to an enormous number of other creatures. It is impossible to eat without harming someone, somewhere along the line. And it takes a very long line to make food, any food. Much longer, and much more harmful than vegans tend to think or are ready to admit.

Vegan Harms

Each agricultural area was once the living space of other creatures, who were killed, chased away, starved (as people have destroyed their food sources), dried (as people took control over their water sources), being exposed to predator (as people have destroyed their dens and other hiding places), restricted by fences, polluted by chemicals, and even burned alive during slash-and-burn. All this happens all the time. Billions of animals are constantly being poisoned, starved, dehydrated, chased away, polluted, trampled by tractors, combines, ploughs and harvesters, their homes are being destroyed and etc. All are common harms inherent to agriculture, and happening every single moment.

The most direct, immediate and familiar harm of plant based agriculture is the spread of poisons such as pesticides, herbicides, insecticides and fungicides. More than 2.5 million tons of poisons are spread all over the world every year. Each gram is aimed to kill any creature in the area, and any potentially “competitive” plant in the area. Much of these poisons also harm creatures living far from the originally sprayed farms, as chemicals tend to drift by wind and washed by rain. The estimation is that almost 100 million fish and birds die each year from pesticide poisoning, and about a billion are harmed by it.

Other types of chemicals intensively used in agriculture are fertilizers, some of which are made out of animals. Most fertilizers are synthetic, but some, mainly in organic farms, are made of animals’ bones, blood, feathers and of course manure. Obviously none of which are originated from wild animals who died naturally, but from factory farmed animals who were tortured and murdered. So anyone who wants to avoid the use of synthetic fertilizers (because they evaporate or are washed and so pollute ecosystems outside the farms, mostly aquatic ones), is bound to indirectly subsidize factory farming, by making animals exploitation more profitable.

Although indeed most of the trees in the rainforests are cut for grazing, they are also cut for growing some of the most basic crops most vegans consume on a daily basis, for example nuts, sugar, tea, coffee, several types of fruits and vegetables, and even the most common raw material for most of peoples’ clothes – cotton.

It is theoretically possible to avoid supporting the destruction of rain forests specifically, if people are extremely careful with every detail regarding every food item they consume (including each and every ingredient and each and every phase their food has gone through before they consumed it), however it is absolutely impossible for people to avoid their share in land clearing in general.

Meat is notoriously water wasteful, but the production of many vegetables also requires plenty of water. According to the Institute of Mechanical Engineers it takes 17,196 liters of water to produce 1kg of chocolate, 3,025 liters of water to produce 1kg of olives, 2, 497 liters of water to produce 1kg of rice, and about the same amount for 1kg of cotton. It takes 1,849 liters of water to produce 1kg of dry pasta, 1,608 liters of water to produce 1kg of bread, 822 liters of water to produce 1kg of apples, 790 liters of water to produce 1kg of bananas, and 287 liters of water to produce 1kg of potatoes.

Humans’ excessive use of water leaves entire regions dried, and all the creatures living there are left to dehydrate.

Much water is also being used after the cultivation stage. The production of food requires a lot of water for washing, cooking, boiling, cooling industrial machinery and etc. But probably the most harmful aspect of food processing is energy, which is obviously inherent to each and every part along the process of each and every food item. Almost each and every food item goes through several processing stages. Many require removal of unwanted parts, cleaning, grinding, liquefaction, drying, sorting, coating, supplementation of other ingredients, cooling, heating, baking, steaming, freezing and etc. All stages are energy-intensive, and the vast majority of it comes from fossil fuels.

But even if it didn’t, energy production methods other than fossil fuels are also harmful. Hydraulic dams for example dehydrate entire habitats, wind turbines are responsible for many bird killing, solar panels are composed of heavy metals, but they are still less harmful than fossil fuels, yet humans, as usual, choose the most harmful option. And since there is little control over the chosen energy production method used for each food item, people are bound to participate in severely harming other creatures. They can’t really even choose the least harmful method, and most certainly can’t choose a harmless one, as there is no such thing.

Another stage in food production that is responsible for a lot of energy consumption (maybe even the most) is food transportation.

Each person in the world contributes in one way or another to what is referred to as the food superhighway. The food superhighway never stops moving. It is made possible by a vast network of ship lanes and flight paths. Without it vegans would run out of most of their food. On any given moment there are 6 million containers moving around the globe. Each and every country is highly depended on long-distance food, so everyone, everywhere participate in a global food system.

Some foods travel thousands of miles during the process stage only, before they are sent all over the world as export. It is very difficult to accurately calculate the mileage of each food item since many foods are composed of several ingredients which each has travelled long distances as well. From the field to the first processing stage, than to the next processing stages, then to the pack house, then to the storage warehouse, and only then to the airport or harbour. All that is for each ingredient of each final food item.

Avoiding all food items that cause air pollution, water pollution, noise pollution, climate alteration, land alteration, land clearing, land destruction, trampling, water waste, poisoning and etc., is simply impossible.

And obviously it’s not just food. It takes more than 33 liters of water to produce just one of the ‘chips’ that typically powers laptops, smart phones and iPads. A single smartphone requires 240 gallons of water to produce. And it even goes further than that as every bit and byte people consume over the internet has an indirect cost in terms of water waste due to the enormous cooling demand in data centers.

Highly environmentally aware vegans might succeed in totally avoiding the use of plastics, but it is hard to avoid the use of metals. An average American consumes about 45,000 pounds of metal (through the consumption of various products) during a lifetime. Each pound of metal must be mined, processed, transported and manufactured into consumable products, all stages are considerably polluting. For example, currently, about 25,500 tons of silver are consumed every year. There is some of it in every car, computer and phone, as well as many other products.

The extraction of raw materials which includes drilling, digging, cutting, refining, and smelting, releases chemical substances and carbon dioxide, and pollute the air, water and land. It also destroys habitat for innumerable animals.

Another unavoidable action for every human, including the most considerate and aware vegans, is sewage. Every day each person produces 20 gallons of sewage. Over a lifetime, that is 567,575 gallons.

Each person sends about 64 tons of waste to landfills over a lifetime. Highly aware and considerate vegans can try their best reducing their share, but it is unavoidable to produce some waste, and it is impossible to prevent much of it from being sent indirectly to landfills.

People harm others even when they clean themselves. Detergents can have poisonous effects on all types of aquatic life if they are present in sufficient quantities, and this includes the biodegradable detergents. All detergents destroy the external mucus layers that protect fish from bacteria and parasites, plus they can cause severe damage to the gills. Most fish will die when detergent concentrations approach 15 ppm (parts per million).

The fact that veganism is less harmful than other options doesn’t make it harmless. So although highly environmentally and socially aware plant based diet is the best option for reducing harms of an existing person, the fact that harms can only be reduced but never avoided serves as a very good reason to never create a new person. There is no way not to harm, even for highly environmentally and socially aware vegans, and therefore there is no way to morally justify creating new people even if they would always be highly environmentally and socially aware vegans themselves.

Maybe part of the problem is because vegans tend to classify harms which are not caused in factory farms, laboratories, or by the use of animals in the clothing industry, and in the entertainment industry, as environmental harms, or even worse, as harm to the environment. But obviously humans don’t harm the environment as there is no such option. The environment is not a moral entity. It is not sentient and it has no interests. The harm is inflicted on sentient creatures. Therefore, ethical vegans can’t overlook these harms claiming that they are not caused to individual sentient animals (who obviously they themselves believe have rights). They can’t exempt themselves from ‘harms to the environment’ because there is no such thing, it is always individual sentient animals who are harmed and so they must take these harms very seriously.

The harm humans inflict on other sentient creatures is so vast that practically there is no human action in modern society that doesn’t harm an individual, an animal person, somewhere in the world.

Ethical vegans claim that veganism is not about being perfectly harmless as it is impossible, but about reducing harms. They may justify causing harms to others by claiming that they can’t exist without harming others, but they can’t justify the creation of new people by claiming that they also can’t exist without harming others, since while their own existence was forced on them, the existence of their children is of their choice. It may be plausible to argue that the harm they are causing was forced on them, but it is absolutely implausible to argue the same for the harms that their children would cause.

But many vegans rationalize, idealize and sugarcoat their choice to create new people by claiming that they are procreating because they are helping to build a vegan army. As ridiculous as it sounds to every reasonable person with some common sense, this fallacy is seriously claimed by many.

This claim brings me to what I find most disappointing about ethical vegans who procreate.

Army of Excuses

What disappoints me the most, at least when it comes to activists, is not the self-deception regarding the real reasons behind their procreation, not the double standard, not the irresponsibility (as there is absolutely no guarantee that their children would stay vegan), and not even the ignorance regarding how much suffering every vegan causes, but the decision to invest so much time and so much energy and resources in just one person, all the more so in one who didn’t need any attention before being created, while there are so many other sentient creatures who already exist and are in an extremely urgent need of help. Why create another need and frustration center when there are already billions of them out there, some desperate for any help possible?

Every activist knows how desperate activists are for any help, and how important each activist is, so deciding to so dramatically divert one’s time, energy and resources to someone who needs it only because they have created that person, despite that it needed nothing before they have decided to create it, is adding problems to a world already full of problems. It is deciding to create another creature which would harm others merely by existing, and who would draw its activist parents’ time and resources from causes that existed before and regardless of its creation. Therefore procreation by ethical vegans is not only hypocrite, untruthful and disappointing, it is also cruel.

Every activist knows how desperate activists are for any help, and how important each activist is, so deciding to so dramatically divert one’s time, energy and resources to someone who needs it only because they have created that person, despite that it needed nothing before they have decided to create it, is adding problems to a world already full of problems. It is deciding to create another creature which would harm others merely by existing, and who would draw its activist parents’ time and resources from causes that existed before and regardless of its creation. Therefore procreation by ethical vegans is not only hypocrite, untruthful and disappointing, it is also cruel.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the average cost of raising a child from birth through age 17 is $233,610. This does not include the cost of a college education, and not if the child stays with the parents after the age of 17, as often happens.

And it’s not the only huge financial cost which must be considered. If parents devote on average around 3 hours a day to their children, by the time they turn 18, it sums up to about 20,000 hours.

Other crucial considerations are hard to measure. It is hard to tell how much energy raising children costs but it is surly enormous.

If all that time, money and energy is invested in animal activism, it would surly have a much more positive effect than raising vegan children.

Even the least talented activists ever can turn two people to veganism if they put into it much of their energy, 40,000 hours, and $467,220.

Spending all that by breeding so there would be more vegans is probably the most inefficient way imaginable.

Activists are declaiming similar arguments in their sleep. They are using the same structure of arguments when they are deconstructing excuses not to go vegan, but not when it comes to procreation, since they want to procreate, not because there is any ethical way to justify it.

Not to procreate is to not harm the person created and to not harm others, while procreating is to cause harm to the person created as well as to others. The chances of the child to be happy are very low and the chances that it would be such an efficient activist that it would worth all the harms caused by it and for it, are very very low. It is much more probable that the person created by vegans would nevertheless cause more suffering than it would reduce (as many children would choose not to be activists at all, and so would only cause suffering and won’t reduce any), and would have more negative experiences than positive ones. Most people, even ones without exceptional problems, are frustrated, bored and dissatisfied most of the time. Most are not satisfied with their jobs, their social life, their intimate relationships, and there is a huge gap between their expectations of themselves and of the world, and what their actual lives are like. Even without exceptional problems and life of misery, it is easy to see that most people are dissatisfied. While all that is the case for every person, since some ethical vegans are claiming that they intend their child to be an activist, that means they are adding an enormous weight on the shoulders of their children, and expose them to the horrors of the world. Animal rights activists are suffering because of what they have been exposed to, why the fuck do they want to do that to their children?!

At some point the vegan parents would have to tell their children why they are vegans, they would have to tell them that most of the people in the world insist on torturing animals just so that they can enjoy the taste of their meat. If they want their children to stay vegan the truth can’t be whitewashed, and telling the truth about the horrible world they were forced into would definitely leave a mark.

Don’t get this the wrong way, I am not claiming that people who are exposed to the horrors of the world are the victims, as obviously the creatures that these horrors are inflicted upon are the victims, but why create someone to later burden that person with such a heavy duty as changing the world, and while exposing all its horrors, instead of focusing on existing people who probably already know much about it, and would otherwise continue being the victimizers?

Even if, for the sake of the argument, I will ignore the problems involved in turning your children into a means to an end (in this case it is not even using someone for something, it is creating someone for something), there is no guarantee that the assignment of the created children to changing the world would ever succeed. The persons created might be totally unfit for being the activists expected of them. And there is not even a guarantee that the person created would even stay vegan, not to mention not harm others, and surly not that it would be such an amazing and efficient activist that any harm caused by that person would be worth it. There is no guarantee for any of that, but there is one regarding the harms caused by that person, they are guaranteed.

On the other hand if people would devote the same time, energy and resources to turning themselves and other people who already exist (and so the harm caused by them is already given), into super-efficient activists, it would be much more sensible, efficient and morally justified than creating new people, who would cause a lot of harm, and maybe would also reduce some if they would become activists and really stay vegan for life.

The claim that if good people would procreate then there would be more good people, is not convincing. If good people would invest all the time, energy and resources that is needed to raise a child only in its first year, on making the world a better place, considering all the harms that their child would cause, it would probably make the world a better place even if their child would grow up to be an activist. And no one creates a child for it to be the vegan messiah. Not even very dedicated vegan activists. If a vegan messiah is needed activists should focus on making themselves one, not on biologically creating one. And if they feel that being a vegan messiah is beyond their ability, why would they think that it is in their power to biologically create one?

Obviously some of the created people would be caring and help others who are in need. But if people think that their children might help others it means they understand that there are others who need help, so it makes much more sense to help others directly than it is to create more people with needs who might help others someday, but also might not, and might even make the world worse, and would definitely harm others by existing, and by reducing the ability of the parents (who seemingly created that person to help others) to help others. That is a very strange and inefficient way to help others.

Procreation by ethical vegans is extremely disappointing because it diverts energy, time and resources from those who already exist and are in need, to those who needed nothing, were deprived of nothing, and harmed by nothing before they were forced into existence.

Antinatalists must be vegans by definition (otherwise they are directly and personally supporting procreation of animals), and ethical vegans, although not by definition but certainly logically and morally, must be antinatalists. But we are not even there yet. The desire to procreate is so strong that even many ethical vegans do it. What is supposed to be absolutely obvious is absolutely not.

The fact that such lame excuses are being used by ethical people who devote most of their lives to reduce suffering, goes to show how strong the procreation urge is. If it is hard to convince even ethical vegans – people who care deeply about the suffering of others – not to procreate, what are the chances to ever convince people who still eat veal and shark soup? There is no chance, and therefore the solution mustn’t rely on people’s willingness to do the right thing, but on the endless commitment, ingeniousness and moral passion of few activists who care enough to try and end procreation for good.

References

Ash, M.; Livezey, J. and Dohlman, E. (2006). Soybean backgrounder. USDA: Economic Research Service. Retrieved from United States Department of Agriculture

audubon.org/news/will-wind-turbines-ever-be-safe-birds

bbc.com/news/science-environment-36492596

Biomass use, production, feed efficiencies, and greenhouse gas emissions from global livestock systems. PNAS, 110, 52

carbonpositivelife.com

ChartsBin statistics collector team (2013). Current worldwide annual meat consumption per capita. Viewed 29 February 2016 from ChartsBin

ciwf.org.uk/media/5235306/The-life-of-Broiler-chickens.pdf

cleancult.com/blog/pollutants-in-laundry-detergent

Consumer Ethics, Harm Footprints, And The Empirical Dimensions Of Food Choices 2015 by Mark Bryant Budolfson

container-recycling.org/index.php

countinganimals.com/a-child-raised-to-weigh-five-hundred-pounds-by-age-ten

countinganimals.com/the-fish-we-kill-to-feed-the-fish-we-eat

countinganimals.com/the-forgotten-mothers-of-chickens-we-eat

countries and production systems. Water Resources and Industry, 1-2, 25-36.

darksky.org

detergentsandsoaps.com

ecowatch.com/u/ecowatch

encyclopedie-environnement.org/app/pdf?idpost=6884&idauthor=A-38&urlimg=%2Fapp%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F10%2Fpollution-lumineuse_couverture.jpg

epa.nsw.gov.au/wastegrants/organics-infrastructure.htm

Ercin A.E., Aldaya M.M. and Hoekstra A.Y. (2012). The water footprint of soy milk and soy burger and equivalent animal products. Ecological equivalent animal products. Ecological Indicators, 18, 392-402

Eshel G., Shepon A., Makow T. and Milo R. (2014). Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas, and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs, and dairy production in the United States. PNAS, 111, 33, 11996-12001

FAO Save Food Global Food Waste and Loss Initiative

fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en

fao.org/zhc/detail-events/en/c/889172

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations Statistics Division 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2016 from FAO Stat

Food, the Environment, and Global Justice 2017 by Mark Bryant Budolfson

FoodBank Hunger Report 2018

foodmiles.com

forbes.com/sites/jimhenry/2016/11/26/millions-more-cars-on-the-road-and-not-just-for-thanksgiving

globalissues.org/article/214/stress-on-the-environment-society-and-resources

Good K. (2014). The surprising way your diet can fix the soy and deforestation problem. One Green Planet. Retrieved from One Green Planet

growveg.com/guides/the-high-cost-of-the-food-superhighway

Herrero M., Havlíkb P., Valinc H., Notenbaertb A., Rufinob M.C., Thorntond P.K., Blümmelb M., Weissc F., Graceb D. and Obersteinerc, M. (2013)

Hoekstra A.Y. (2012). The hidden water resource use behind meat and dairy. Animal Frontiers, 2, 2

Hoekstra and Chapagain, 2008, cited in Ercin A.E., Aldaya M.M. and Hoekstra A.Y. (2012). The water footprint of soy milk and soy burger and equivalent animal products. Ecological Indicators, 18, 392-402

independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/veganism-environment-veganuary-friendly-food-diet-damage-hodmedods-protein-crops-jack-monroe-a8177541.html

independent.co.uk/news/science/environment-extinction-elephant-giraffe-rhino-hippo-biodiversity-animal-history-a8859746.html

International Dark-Sky Association. “International Dark Sky Places.” Accessed November 19, 2013. darksky.org/night-sky-conservation/34-ida/about-ida/142-idsplaces

Mekonnen M.M. and Hoekstra A.Y. (2012). A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems, 15, 401-415. DOI:10.1007/s10021-011-9517-8

modernslaveryhelpline.org

National Soybean Research Laboratory NSRL. Benefits of soy. Retrieved from: NSRL.

nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/06/plastic-planet-waste-pollution-trash-crisis

One Green Planet (2012). Facts on animal farming and the environment. Retrieved from One Green Planet.

ozharvest.org

peta.org/issues/animals-used-for-food/factory-farming

Piazza J., Ruby M.B., Loughnan S., Luong M., Kulik J., Watkins H.M. and Seigerman M. (2015). Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite, 91, 114-128

Pimentel D., Berger B., Filiberto D., Newton M., Wolfe B., Karabinakis E., Clark S., Poon E., Abbett E. and Nandagopal S. (2004). Water resources: Agriculture, the environment, and society. BioScience, 47, 2, 97-106

Pimentel D., Houser J., Preiss E., White O., Fang H., Mesnick L., Barsky T., Tariche S., Schreck J. and Alpert S. (1997). Water resources:Agriculture, the environment, and society. BioScience, 47, 2, 97-106

plasticpollutioncoalition.org

shrinkthatfootprint.com/food-miles

Smil V. (2014). Eating meat: Constants and changes. Global Food Security, 3, 2, 67-71 dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.06.001

smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-many-birds-do-wind-turbines-really-kill-180948154

Steinfeld H., Gerber P., Wassenaar T., Castel V., Rosales M. and de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. Retrieved from FAO

studyfinds.org/children-climate-change-save-planet

Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment by David Pimentel and Marcia Pimentel the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

theguardian.com/environment/2011/jan/12/vegetarians-food-animal-origin-fertiliser-vegetarian

theguardian.com/environment/2013/jun/30/stephen-emmott-ten-billion

theguardian.com/environment/2017/jul/12/want-to-fight-climate-change-have-fewer-children

theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/28/a-million-a-minute-worlds-plastic-bottle-binge-as-dangerous-as-climate-change

treehugger.com/green-food/homemade-bone-meal-a-partial-solution-to-peak-phosphate.html

treehugger.com/green-food/vegan-organic-agriculture-is-your-carrot-really-vegan.html

treehugger.com/lawn-garden/finally-a-practical-guide-to-dealing-withmanure-book-review.html

treehugger.com/renewable-energy/north-america-wind-turbines-kill-around-300000-birds-annually-house-cats-around-3000000000.html

Watch magazine. Retrieved from Worldwatch Institute

Water Foorptint Netweork

What’s Wrong with Industrial Agriculture Environmental Health Perspectives Volume 110, Number 5, May 2002

World Watch Institute (2004). Meat. Now, it’s not personal! But like it or not, meant-eating is becoming a problem for everyone on the planet

World Watch Magazine, 17, 4. Retrieved from World Watch

Worldwatch Institute (2004). Meat. Now, it’s not personal! But like it or not, meat-eating is becoming a problem for everyone on the planet. World

WWF (2014). The growth of soy: Impacts and solutions. WWF International. Gland, Switzerland

WWF (n.d). Soy – Facts and Data. Retrieved from WWF

Ziegler L. (2015). Keep showering, California. Just lay off the burgers & nuts. Medium. Retrieved from : Medium

Zonderland-Thomassen M.A. and Ledgard S.F. (2012). Water footprinting – A comparison of methods using New Zealand dairy farming as a case study. Agricultural Systems, 110, 30-40

Recent Comments