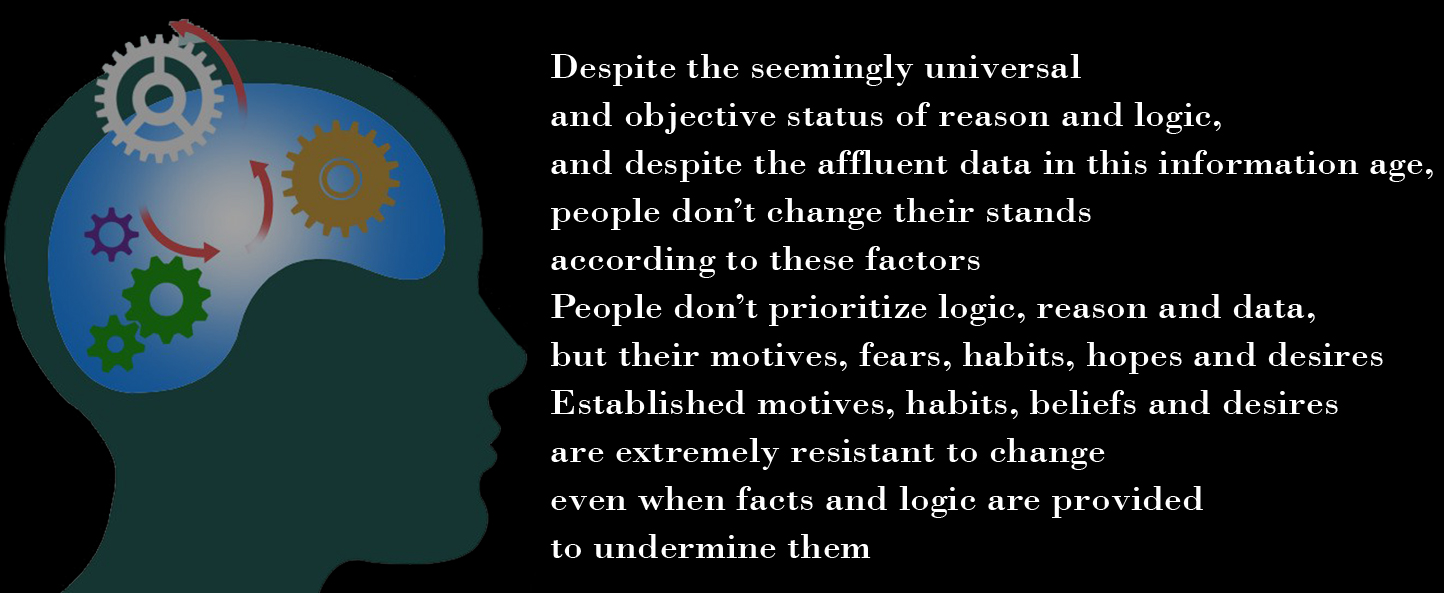

Many activists are misled by the intuition that if people are faced with a rational, logically valid and factually based argument, they would be convinced. However, this is unfortunately not at all the case.

One of the reasons people are not convinced by rational arguments is that people are not rational creatures. I have addressed people’s irrationality in a former text, where I argued that since creating a new person is imposing such a huge risk on someone else, people must be perfect decision makers. However, people are highly influenced by various cognitive biases which affect their perceptions, judgments, reasoning, emotions, believes and decision making, therefore they most definitely must never create new people. In this post I’ll argue that not only that various cognitive biases shape, or at least highly affect, people’s perceptions, judgments, reasoning, emotions, believes and decision making; other cognitive biases make it very hard to change people’s perceptions, judgments, reasoning, emotions, believes and decision making after they have been settled.

The intuition is that when we want to convince someone we must articulately present our logical arguments and support them with facts. But the fact is that it rarely works. It is very rare that the other side of the debate patiently and carefully listens to each of our well thought out factually based arguments.

People are not receiving information objectively and rationally. Every piece of information is filtered by their immediate emotional state (which affects the way this information would be processed in the long term as well), previous perceptions, hidden and explicit motives, will power, interests, how this information is delivered, and by whom this information is delivered (neuroscientists found that the brain encodes information much better when it comes from an agreeing partner). Information is never an independent standalone true reflection of reality, but always a filtered representation of it. By that I don’t mean that every case of information communication is somehow biased (although indeed it is almost always the case) but that every case of information receiving is somehow biased. And the strongest and most common bias for that matter is the Confirmation Bias, and therefore is the central issue of the following text.

The Confirmation Bias

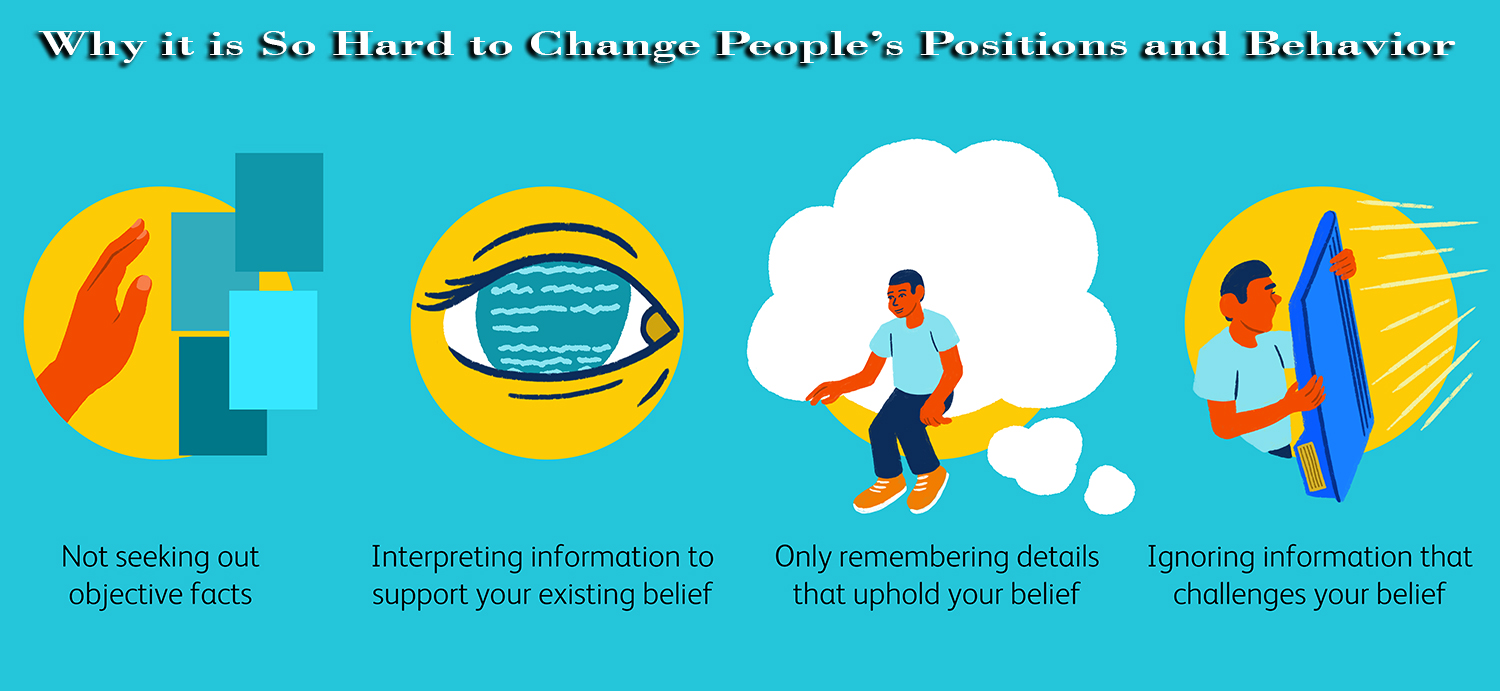

People tend to favor, seek out, interpret, and even remember, information in a way that confirms and/or reinforces their positions and behavior, and disfavor and discount (or forget) any information that contradicts or threatens their positions and behavior.

Some scholars call it The Disconfirmation Bias and distinguish it from The Confirmation Bias which according to them is when people simply avoid information which counters their positions. For simplification, I’ll refer to both biases in an integrated manner under The Confirmation Bias, since ultimately, both apply to people’s tendency to maintain their positions, either by avoiding or resisting information that might lead them to reevaluate their beliefs, and/or by seeking information that supports their beliefs, which is uncritically valuated as accurate and reliable.

The confirmation bias doesn’t suggest that people aren’t easily influenced in general. Obviously people are quite pliable, influenced by social norms, trends, peer pressure, groupthink, as well as several other cognitive biases. The confirmation bias suggests that once a person has found desirable and comfortable decisions and beliefs, it is hard for another person to convince that person otherwise, let alone using rational arguments, logic and facts.

Leon Festinger, the psychologist behind the Cognitive Dissonance theory, said that: “A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.”

Evolutionary psychology suggests that the reason people have such a difficulty with being convinced by others, is that in evolutionary sense each individual aspires to increase its own fitness, not to seek the truth. In other words, the important thing is not what is true but what helps individuals to survive and multiply. Evolution is not about truth, it is about fitness.

Some relate this bias to less logical people, to ignorance, or even to stupidity, but in fact people with stronger analytic abilities are more likely to be able to twist any given information in ways that confirm their preexisting positions.

Studies have shown that when people are given two different scenarios in which they must determine the most efficient policy in each, when one scenario is emotionally neutral and the other is emotionally charged, it appears that the people with the best analytic abilities performed best in the emotionally neutral scenario, meaning they used their abilities to carefully and rationally analyze the data, however they performed worst in the emotionally charged scenario, since their preexisting position on the subject interfered with their ability to objectively analyze the data and accurately assess the most efficient policy stemming from it.

That goes to show that motivated reasoning is a universal trait, and not one of the less intelligent people. If anything, as just argued, it is the other way around, better cognitive capacities are more likely to strengthen the confirmation bias, as people with greater abilities for rationalizing and creatively twisting data, are more likely to strengthen their preexisting positions.

Unfortunately people tend to use their intelligence to maintain and support the positions they are more comfortable with, not to draw the most accurate conclusion from any given situation.

That is one of the reasons why we don’t necessarily see a strong correlation between intelligent people and right positions. And why it is not necessarily easier to convince the more intelligent people to embrace the right positions.

Not only that people tend to devalue information which contradicts their prior positions, they often distance themselves from such information. They don’t want “the truth” but “their truth”.

They don’t seek out the information which is most likely to be accurate, but the information which is most likely not to impact their habits, beliefs and behavior.

And that’s exactly what us antinatalists are trying to do. We are not only trying to fight against people’s desires, we are fighting against how their brain works. As mentioned in the text about The Optimism Bias, bad news and good news are not encoded in the same areas of the brain, and good news are encoded better than bad news. The brain treat bad news like a shock and good news like a reward, so it is no surprise that people seek for, focus on and remember good news, and that they always try to avoid, disregard and forget bad news.

When we are telling people that bad thing will happen to them, or to their children, unconsciously, their brain vigorously distort that information until it gets a satisfying picture.

People tend to seek out positive information that brings them hope and to avoid negative information such as the chances that their children would be harmed, not to mention information which compels them to do things they don’t want to such as not creating children.

People tend to avoid and/or distort gloomy messages. That doesn’t mean we should avoid presenting gloomy facts, but that it is not very likely to succeed. We can spend weeks formulating the best arguments, refer to the best articles and books, and assemble the most unequivocal data to support it, but eventually it doesn’t matter how good our work is if people don’t want to listen, not to mention are not even slightly open to be convinced.

So us presenting our case in the best way possible is insufficient to change other’s minds. That is because convincing is not only about the message or the messenger, but it is largely about the receiver, and about the receiver’s current mood, and mental state. The receiver’s emotional state is highly crucial since it highly affects perception, reasoning, and decision making.

That means that a person can be convinced or not convinced, by the very same argument and data, depending on the particular emotional state that person was in at the time of encountering it.

Making things even worse is the idea of ‘arbitrary coherence’ which is mostly attributed to economics but it is also relevant to beliefs and decision making. The basic idea in economics is that although the initial price of a product is often arbitrary, once it is established in one’s mind, it will affect the way not only the price of this product is assessed, but also future prices of related products, supposedly to make these prices “coherent”. But this imprinting process is relevant in other areas as well. Not only that many of people’s initial decisions are arbitrary, and are highly influenced by people’s emotional state during these initial decisions, people tend to stick to their initial decisions, which also affect future decisions of related issues. People’s first impressions and decisions become imprinted, and this arbitrary primacy has a tremendous effect on other decisions in the long-run.

That means that if an antinatalist talks to a person about procreation when that person is irritated, impatient, or particularly joyful in that day, that person might develop baseless arbitrary negativity to the subject and in later encounters that person would not only be biased by its preexisting positions but also by its desire to be consistent (as well as by pride and ego which tackle that person ability to admit s/he is wrong), and all these forces cause even the more open, caring and rational people to close their minds.

It is very rare that people say ‘maybe I was wrong about that’, or ‘now that I see the whole picture I surly must change my mind’. As the confirmation bias suggests (and surly your experience with trying to convince others supports), people usually tend to organize the facts according to their stands, not the other way around.

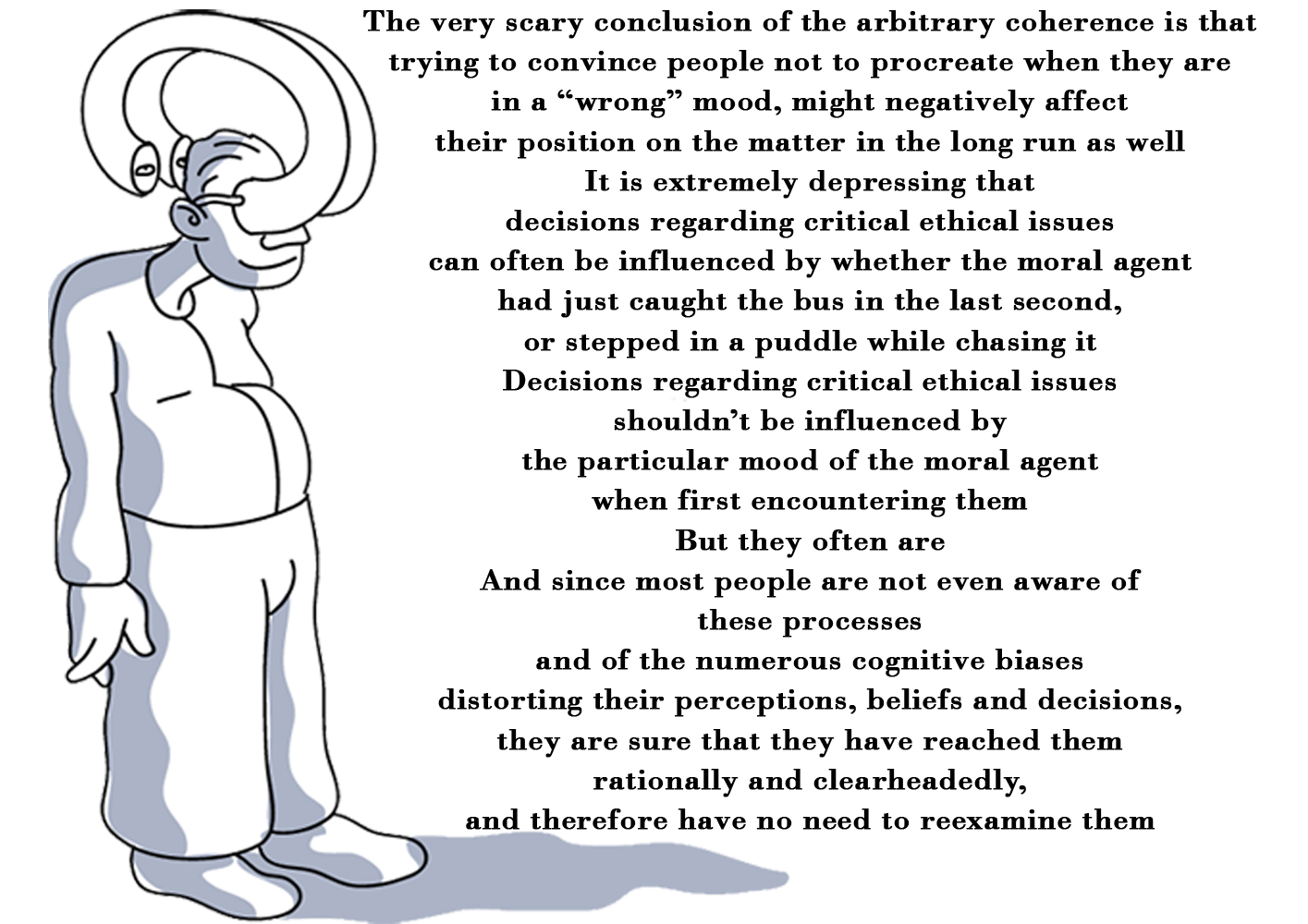

So the very scary conclusion of the arbitrary coherence is that trying to convince people not to procreate when they are in a “wrong” mood, might negatively affect their position on the matter in the long run as well. It is extremely depressing that decisions regarding critical ethical issues can often be influenced by whether the moral agent had just caught the bus in the last second, or stepped in a puddle while chasing it.

Decisions regarding critical ethical issues shouldn’t be influenced by the particular mood of the moral agent when first encountering them. But they often are. And since most people are not even aware of these processes and of the numerous cognitive biases distorting their perceptions, beliefs and decisions, they are sure they have reached them rationally and clearheadedly, and therefore have no need to reexamine them.

Other Related Biases

Other cognitive biases which make it extremely hard to change people’s beliefs, ideas, decisions and behavior are:

The Bandwagon Effect which refers to people’s tendency to believe and do things regardless of any supportive evidence but merely since others believe and do them.

While this psychological phenomenon is seemingly mostly about why people adopt beliefs, ideas and behavior, and not why they don’t change them, given that people have a strong tendency to conform, they find it hard to resist or hold positions which are counter to the norm, and in relation to this text, it is hard to convince them to change their beliefs, ideas and behavior, no matter how false, ridiculous, and refutable they may be, as long as they are synched with most of the others.

Conformity and social pressure don’t only cause people to adopt normative beliefs, ideas and behavior, but also to resist non-normative ones. Conformity is not only causing more and more people to “get on the bandwagon” when something’s popularity increases, but also to less and less people to get off of it once they are on it.

Conformity is an extremely powerful phenomenon. Solomon Asch’s experiments conducted in the 50’s, and many more conformity experiments which have been replicated more than 130 times in many different countries, all have the same overall outcome and with no significant differences across nations – people are confirming obvious errors about one-third of the time. And that is the pattern when the task is very simple, and the error is extremely obvious (when people were asked the same questions when they were by themselves they almost never erred). It is frightening to think what would be the confirmation rate had the task been a bit more challenging than identifying which line is longer, and had the people who deliberately gave an incorrect answer weren’t strangers whom the tested would probably never see again, but people they know and trust.

According to the System Justification Theory, people are not only motivated to conform, but also to defend, bolster, and justify (often unconsciously) the social, economic, political, and ethical systems they currently live in, even if they don’t personally benefit from them, because justifying the status quo serves as psychological sooth for epistemic, existential, and relational needs. Viewing the status quo as justified, natural and desirable, even if it enhances inequality, injustice, favoritism and etc., originate in people’s need of order and stability, and in their need to hold positive attitudes about themselves, about the groups they belong to, and according to the theory, also about the social structure they are a part of.

Favoring the status quo reduces uncertainty, threat, and social discord. It also functions as a coping mechanism for dealing with inevitable negative situations, since being biased to favor an existing reality which is beyond people’s control, makes people feel better about it. This manifestation relates to people’s tendency of valuating events as more desirable, not according to their intrinsic value, but according to their likelihood to occur.

And thus, resistance to the status que, and alternatives to the current system, are disapproved and disliked.

Another related effect, which is similar but not the same as the Confirmation Bias, is the Continued Influence Effect. This effect, which is also known as the Continued Influence of Misinformation, refers to the fact that false claims and misinformation, once heard, often continue to influence people’s thinking and feelings long after they have been proven false. Internalized claims and pieces of information are not easily forgotten, even if they are ridiculously untrue and were utterly refuted. So not only that we must fight against false claims and misinformation derived from biological urges, cultural norms and conformity, we must also try to refute false claims and misinformation simply because they are there.

And not only that, these beliefs, ideas and behaviors can often be strengthened when others try to refute them. That is called the Backfire Effect or the Boomerang Effect. Ironically and irrationally, but not surprisingly, when people’s beliefs are challenged by contradictory evidence, they often get stronger. The researchers who named the Boomerang Effect (Hovland, Janis and Kelly) in 1953, argued that it is more likely under certain conditions, for example when the persuader’s position is so far from the recipient’s position that it would enhance the recipient’s original position. Unfortunately that is surly the case when it comes to antinatalism, which as obvious and self-evident as it is to us, it is unobvious and considered nuts by most people.

Another reason why it is so hard to convince people is that they tend to value the validity of arguments according to their personal relation to their conclusion, instead of whether they validly support that conclusion. So people can reject an argument despite that it is valid because they dislike its conclusion. It might seem intuitive and rather reasonable, but thinking about it, what’s the point of logic if a logical argument can be rejected merely because people don’t want to accept its logical and valid inference?

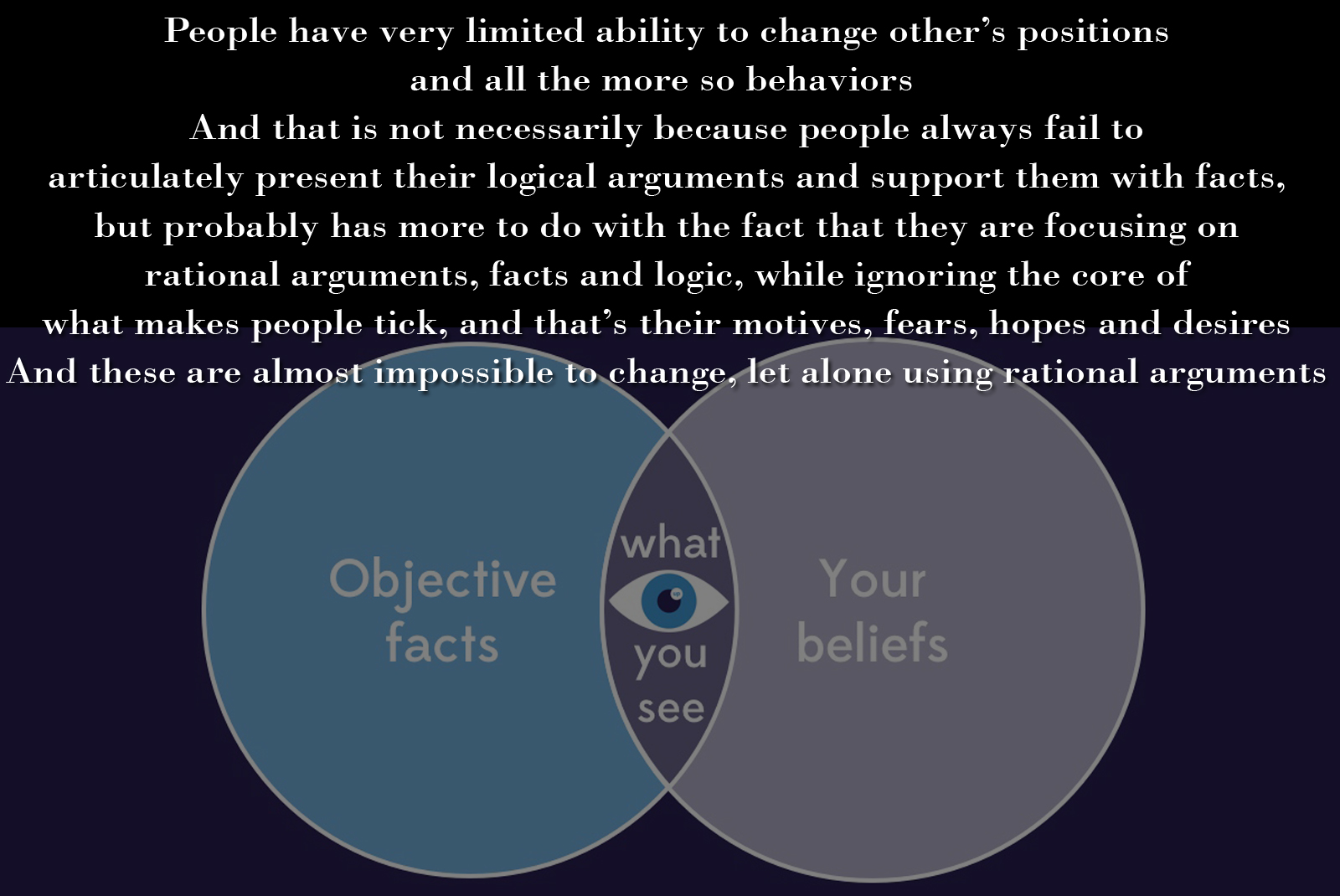

In conclusion, people have very limited ability to change other’s positions and all the more so behaviors. And that is not necessarily because people always fail to articulately present their logical arguments and support them with facts, but probably has more to do with the fact that they are focusing on rational arguments, facts and logic, while ignoring the core of what makes people tick, and that’s their motives, fears, hopes and desires. And these are almost impossible to change, let alone using rational arguments.

Rational arguments rarely work, and even that is relevant for a relatively small minority of people. For the rest, rationality is irrelevant and useless. So we must focus on other, more useful ideas to tackle the problem.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company

Dardenne B, Leyens JP (1995). “Confirmation Bias as a Social Skill”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 21 (11): 1229–1239. doi:10.1177/01461672952111011

de Meza D, Dawson C (January 24, 2018). “Wishful Thinking, Prudent Behavior: The Evolutionary Origin of Optimism, Loss Aversion and Disappointment Aversion”. SSRN 3108432

Donna Rose Addis, Alana T. Wong, and Daniel L. Schacter, “Remembering the Past and Imagining the Future: Common and Distinct Neural Substrates During Event Construction and Elaboration,” Neuropsychologia 45, no. 7 (2007): 1363–77, doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

Enzle, Michael E.; Michael J. A. Wohl (March 2009). “Illusion of control by proxy: Placing one’s fate in the hands of another”. British Journal of Social Psychology. 48 (1): 183–200

doi:10.1348/014466607×258696. PMID 18034916

False Uniqueness Bias (SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY) – IResearchNet”. 2016-01-13

Gilovich T (1993). How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-911706-4

Gino, Francesca; Sharek, Zachariah; Moore, Don A. (2011). “Keeping the illusion of control under control: Ceilings, floors, and imperfect calibration”. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 114 (2): 104–114. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.10.002

Jonathon D. Brown and Margaret A. Marshall, “Great Expectations: Optimism and Pessimism in Achievement Settings,” in Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice, ed. Edward C. Chang (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2000), pp. 239–56

Kokkoris, Michail (2020-01-16). “The Dark Side of Self-Control”. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 17 January 2020

Kruger J, Dunning D (December 1999). “Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77 (6): 1121–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.64.2655. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121. PMID 10626367

Kruger J (August 1999). “Lake Wobegon be gone! The “below-average effect” and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77(2): 221–32. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.221. PMID 10474208

McKenna, F. P. (1993). “It won’t happen to me: Unrealistic optimism or illusion of control?”. British Journal of Psychology. 84 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02461.x

Michael F. Scheier, Charles S. Carver, and Michael W. Bridges, “Optimism, Pessimism, and Psychological Well-being,” in Chang, ed., Optimism and Pessimism, pp. 189–216

Nickerson RS (1998). “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises” (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 2 (2): 175–220 [198]. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Oswald ME, Grosjean S (2004). “Confirmation Bias”. In Pohl RF (ed.). Cognitive Illusions: A Handbook on Fallacies and Biases in Thinking, Judgement and Memory. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. pp. 79–96. ISBN 978-1-84169-351-4. OCLC 55124398

Pacini, Rosemary; Muir, Francisco; Epstein, Seymour (1998). “Depressive realism from the perspective of cognitive-experiential self-theory”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (4): 1056–1068. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.1056. PMID 9569659

Thompson, Suzanne C.; Armstrong, Wade; Thomas, Craig (1998). “Illusions of Control, Underestimations, and Accuracy: A Control Heuristic Explanation”. Psychological Bulletin. 123 (2): 143–161. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.143. PMID 9522682

Leave a Reply